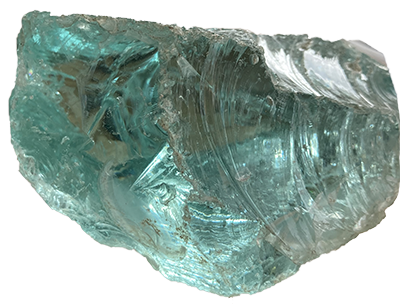

Wet rooms, or a maple table with a deep sea-blue green glass top

There is a photo by Nan Goldin that I can’t get over. It’s called Valerie in the light, Bruno in the dark (2001) and what I like about it is that it’s the kind of picture where the light itself is the thing you remember after seeing it: a broad buttery slab that takes up two thirds of the frame. One effect of this illumination is that the surface textures in the image become the focus rather than the human figures. Valerie’s dress, hair, skin, and a square of wall behind her are all lit up. When I try to picture it without looking it up again I think the whole thing could be made of metal, palladium or nickel or just gold-gold.

The work detail that I first saw from Laps, pullbuoys and plunge pools was on a phone screen. There was a tiny animated octopus sticker moving across it, with soft backward jet propulsion from all of its arms at once. The pairing felt right: the work was an ocean of dusty coral but also it was like dry ice, and immersed in either the octopus looked as if it would thrive. Because the whole image was cropped to instagram story dimensions, it felt taller or deeper than the final work would. Looking at it was also looking into it, like right up close into a backlit fish tank, or through goggles at the water tearing apart as you plunge into a deep pool, rather than at a work on a screen with edges. Later, when I see another story of a work with rope knotted taut across it, its edges still not visible, I get that feeling you do when you tie your hair back, or put your watch on: less vulnerable and more decisive. It is true I also miss the octopus.

The woman in the photo is Valerie Massadian, Nan Goldin’s friend and a filmmaker. She reappears in many other photographs, floating in a dark sea, looking worried in a taxi; they edited a book together. When we watch the Laura Poitras documentary about Goldin’s protest against the Sackler family profiting from OxyContin addiction, I anticipate seeing Valerie again there—I expect she will be older, or perhaps not sober, or blurred in a hallway, but with the same eyebrows—and when I don’t I recognise that it’s a rare and flinty form of luck to have the same friends in the foreground of your photos this year and last year and next year even as the hallways and plates and bottles and seasons change around them.

From the earliest time I remember speaking with Emma about her work there were groups of people and friendships connected with it, not explicitly but always present, something like how a jacket retains body warmth just after it’s taken off. When we talked about art history I felt that suddenly there were rooms and rooms and rooms, stretching back in time, filled with queer women who were talking too, or walking. Or actually flying, across courts in garments that unfurled and reformed around them like diagrams. Or swimming laps, consistent as clocks, across rectangular lane pools.

This new work continues to remind me of rooms and spaces I've seen only in films or photographs. I think of Eileen Gray’s L-shaped E-1027 and its roof terrace that looks out to the sea at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. I think about the house Agnes Martin built with adobe bricks, huge wooden roof beams that she brought home in her truck. I read that there was just one poster on the walls inside, a painting by her friend Georgia O’Keeffe. I think of Georgia O'Keeffe's Ghost Ranch in New Mexico, sagebrush and bitter chamiso scrawled in the foreground of sun bleached photos, and a feeling of baked heat. Seeing the harder gleam of materials like chrome or cellophane in the new work, I think of how these materials have transformed earlier rooms,

Sometimes it’s an imagined or future architecture that Emma’s work brings to mind; always, there are canvas awnings, wide-open windows, screens that filter and slice or soak the light according to the day. Height-adjustable circular glass tables and a globe lamp, a chair that S-bends for a reclining body. When I see this new work I think, maybe the pool is another kind of room, something like the wet room where you leave coats and boots, where everything is designed to cope with water?

But pools are different from rooms. They are spaces where your body no longer needs to adopt the angles of chairs, or even clothes, and the movement is horizontal and supported. Laps, laps, laps: the counting that freestyle arms do as they pass through the air above and gouge the water below, analogue timepieces that are not worn, but are the body. And pools are acoustically different too: the metallic tones that you hear underwater (I always think of someone dropping jewellery), the sound of your own breathing and your body dredging through the water. Watching someone swim fast and well, I think it must feel like being chrome-plated, like being an eel or an arrow, but I am not really a swimmer. Most of the images of swimming I have are from conversations with Emma or other regular swimmers. I trust this kind of secondary-knowing even more than my own firsthand experience; the kind that is collectively held between many. The pool chemicals turned my sisters’ hair light green each summer, their eyes bloodshot, and I envied how it made them seem jaded or tired, as I thought teenagers should look. If a pool is at all like a room, it is one where you can elude all of the edges, or, where the only edge that matters is your skin, the skin of an animal made for water.

Another writer, of another photo, writes “Light wraps the photo like a bandage on fire.”2 The image of Blue Ribbon View arrives in my inbox like this, both luminous and abruptly. Seeing it I worry that i’ve not realised earlier that paintings can be like this, like sport or fire or adrenalin, and that i’ve gotten caught up with thinking of square cold wet rooms and the clock-like precision of swimmers’ arms, hard-edged buildings, a photograph of someone else’s friend in an old afternoon. A work like this is not a room, something that contains you. It is the moment after the plunge into cold water, after the downward vertical, when you erupt back up into the air and the light itself explodes around you like blood vessels.

The work detail that I first saw from Laps, pullbuoys and plunge pools was on a phone screen. There was a tiny animated octopus sticker moving across it, with soft backward jet propulsion from all of its arms at once. The pairing felt right: the work was an ocean of dusty coral but also it was like dry ice, and immersed in either the octopus looked as if it would thrive. Because the whole image was cropped to instagram story dimensions, it felt taller or deeper than the final work would. Looking at it was also looking into it, like right up close into a backlit fish tank, or through goggles at the water tearing apart as you plunge into a deep pool, rather than at a work on a screen with edges. Later, when I see another story of a work with rope knotted taut across it, its edges still not visible, I get that feeling you do when you tie your hair back, or put your watch on: less vulnerable and more decisive. It is true I also miss the octopus.

The woman in the photo is Valerie Massadian, Nan Goldin’s friend and a filmmaker. She reappears in many other photographs, floating in a dark sea, looking worried in a taxi; they edited a book together. When we watch the Laura Poitras documentary about Goldin’s protest against the Sackler family profiting from OxyContin addiction, I anticipate seeing Valerie again there—I expect she will be older, or perhaps not sober, or blurred in a hallway, but with the same eyebrows—and when I don’t I recognise that it’s a rare and flinty form of luck to have the same friends in the foreground of your photos this year and last year and next year even as the hallways and plates and bottles and seasons change around them.

From the earliest time I remember speaking with Emma about her work there were groups of people and friendships connected with it, not explicitly but always present, something like how a jacket retains body warmth just after it’s taken off. When we talked about art history I felt that suddenly there were rooms and rooms and rooms, stretching back in time, filled with queer women who were talking too, or walking. Or actually flying, across courts in garments that unfurled and reformed around them like diagrams. Or swimming laps, consistent as clocks, across rectangular lane pools.

This new work continues to remind me of rooms and spaces I've seen only in films or photographs. I think of Eileen Gray’s L-shaped E-1027 and its roof terrace that looks out to the sea at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. I think about the house Agnes Martin built with adobe bricks, huge wooden roof beams that she brought home in her truck. I read that there was just one poster on the walls inside, a painting by her friend Georgia O’Keeffe. I think of Georgia O'Keeffe's Ghost Ranch in New Mexico, sagebrush and bitter chamiso scrawled in the foreground of sun bleached photos, and a feeling of baked heat. Seeing the harder gleam of materials like chrome or cellophane in the new work, I think of how these materials have transformed earlier rooms,

…designed by Sara Lipska (1882-1989), [the room] features many modern materials such as aluminum and glass…Highlights of the salon include an aluminum screen, a maple table with a deep sea-blue green glass top, a burnished copper screen and chest, and a rock crystal desk lamp on a wooden base.1

Sometimes it’s an imagined or future architecture that Emma’s work brings to mind; always, there are canvas awnings, wide-open windows, screens that filter and slice or soak the light according to the day. Height-adjustable circular glass tables and a globe lamp, a chair that S-bends for a reclining body. When I see this new work I think, maybe the pool is another kind of room, something like the wet room where you leave coats and boots, where everything is designed to cope with water?

But pools are different from rooms. They are spaces where your body no longer needs to adopt the angles of chairs, or even clothes, and the movement is horizontal and supported. Laps, laps, laps: the counting that freestyle arms do as they pass through the air above and gouge the water below, analogue timepieces that are not worn, but are the body. And pools are acoustically different too: the metallic tones that you hear underwater (I always think of someone dropping jewellery), the sound of your own breathing and your body dredging through the water. Watching someone swim fast and well, I think it must feel like being chrome-plated, like being an eel or an arrow, but I am not really a swimmer. Most of the images of swimming I have are from conversations with Emma or other regular swimmers. I trust this kind of secondary-knowing even more than my own firsthand experience; the kind that is collectively held between many. The pool chemicals turned my sisters’ hair light green each summer, their eyes bloodshot, and I envied how it made them seem jaded or tired, as I thought teenagers should look. If a pool is at all like a room, it is one where you can elude all of the edges, or, where the only edge that matters is your skin, the skin of an animal made for water.

Another writer, of another photo, writes “Light wraps the photo like a bandage on fire.”2 The image of Blue Ribbon View arrives in my inbox like this, both luminous and abruptly. Seeing it I worry that i’ve not realised earlier that paintings can be like this, like sport or fire or adrenalin, and that i’ve gotten caught up with thinking of square cold wet rooms and the clock-like precision of swimmers’ arms, hard-edged buildings, a photograph of someone else’s friend in an old afternoon. A work like this is not a room, something that contains you. It is the moment after the plunge into cold water, after the downward vertical, when you erupt back up into the air and the light itself explodes around you like blood vessels.

Written for Emma Fitts’ exhibition, Laps, pullbuoys and plunge pools at The National, Ōtautahi, 15 May - 15 June 2024.

[1] Description of a dressmaking salon by Sara Lipska, Paris, 1925. Photography by Therese Bonney, held in the Smithsonian Libraries image collection.

[2] Listen to Sterling HolyWhiteMountain reading ‘Labyrinth’ by Robert Bolaño (transl. by Chris Andrews), first published in The New Yorker, 2012.