This is not crying

The lacrimal glands, at the upper and outer edge of each eye, are where tears come from. They sluice the eyeball, some spilling over the lower lid, then drain into two canals at the eye’s inner corner, into the nose and down the back of the throat. I think of this salty watercourse as I watch Ana Iti’s work, I am a salt lake, in the darkness of the gallery. I am not crying but I'm aware that it might look like I am. I am just squinting at the glare of the light-on-salt on the lake edges at Kapara te Hau, Grassmere, and at the intermittent plain white screens that throw their exposing light back onto my face.

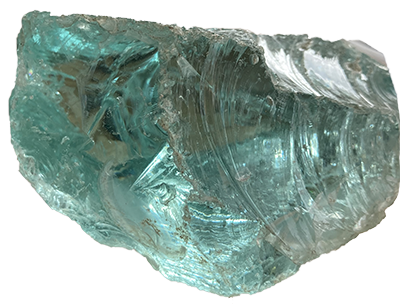

A tears analogy, reduced, could be a useful way to understand the process of salt production. It’s like the ponds used in the production of salt are eyes, excreting tears which ultimately dry as encrusted sodium chloride. The water at Kapara Te Hau actually comes from the sea, pumped into a series of distillation ponds so that the salt can be extracted from it. If you sit with it though, there’s a connection between these processes. That is, both involve the movement of water across a body, and a shift of physical state. Perhaps there is grief involved in both processes too. The extraction of salt from the sea, so that it can be harvested in its crystalline form: this embodies violence like any other mineral extraction. Salt is the easiest way to intensify the savouriness of food, to preserve, bind or emulsify. The salt harvest is perhaps slower and less visible than other forms of environmental extraction, still, the demand for the product is ceaseless, the process itself dramatically marking the land.

Similarly, the production of tears usually occurs at a moment of physical and psychological extremity, a bodily response inextricably connected with the inner self. A form of tangi or crying, as understood within te ao Māori, is articulated with precision in the whakataukī “Wahine tangi haehae, he ngaru moana, e kore e mātaki”. This is translated as “Wailing and laceration of women, mourning like a wave of the ocean, go on unceasingly”. The phrase is discussed by Leonie Pihama, Hineitimoana Greensill, Hōri Manuirirangi and Naomi Simmonds in their publication, He Kare-ā-Roto:

The ritual of mourning is a natural part of life and death in Te Ao Māori, with mediums such as waiata-tangi, apakura and mōteatea heavily laden with references to grief and loss. It was once common within Māori society for women to express this grief not only through wailing, but also the physical act of ‘haehae’, which involved the laceration of limbs, body parts and even the face with flakes of obsidian. This practice was custom following the loss of a loved one, and like the relentless tides of the ocean, women could be heard wailing during tangihanga whilst bearing the sacred wreathes of the pare kawakawa.1

Significantly, the tangi or crying, the voice itself, is positioned in relation to the ‘relentless tides’ of the sea, and in relation to other kinds of pain, some self-inflicted with shards of volcanic glass, obsidian. There is no separation here between the internal experience of grief and its physical embodiment. Further, in the reo Māori version at least, the word ‘like’ is not used: rather, the waves are the tangi. I think of my own mother, writing after dad’s death: “My heart is a stone that beats”. I understand now why she collected so many rocks around that time, weighing down all our windowsills.

*

The first trip to Kapara te Hau for filming was difficult. Ana described to me the harshness of the environment she met on arriving at the lakes from Blenheim. She stopped the car at the end of the road to the sea, got out, anxious maybe—because you never know if you’re going to get the footage that works, because your girlfriend is waiting in the car, and the camera gear is heavy. There, even the starchy sedge, hebe, pōheuheu that survive seem to cling onto the arid surface, wiry and matted. The light is white and the wind is strong, a prevailing northwesterly coursing down from Cook Strait and drying the area out.

It’s for these conditions that George Skellerup, founder of Para Rubber in Christchurch, in 1942 received government permission and began work to establish a solar salt-works there. Molten salt is used in the process of recycling old rubber; by 1955 Dominion Salt Limited was harvesting 3,000 tonnes of salt each year. Today, salt from these ponds accounts for about half of New Zealand’s salt consumption. Rubber production itself is a violent process: harvested as liquid latex from the para tree, before being acidified, dried, smoked, and accounting for mass deforestation to enable rubber plantations.2 The salt is what enables the next phase in the ‘life-cycle’ of natural rubber, under conditions of extreme heat.

A second trip, in late summer when the salt ponds bloom blood-red with microscopic algae, was easier. Using a drone, Ana and videographer Mike Pointon filmed over three days, recording the area in another season or phase in the cycle of salt production. From above, the ponds look meaty, a carefully regulated series of open wounds in the landscape. Too easy maybe to use these metaphors, after all, all bodies leak, sweat, bleed, excrete. Too easy to think of the expressions ‘rubbing salt in the wounds’ or ‘salt of the earth’, both of which evidence the historical value of salt as an anti-bacterial, and as a necessity. In Kapara te Hau it is the algae, stressed by the increasing salinity, that produces the red as the water evaporates.

Recently I've been thinking about these reds in nature, and their role as an alert or rupture of some kind. The stain of blood on my dad’s shirt as he walked out of the bush on Karioi carrying a dead goat; the bright rust colour of the water that came up from a bore in the ground when our rainwater tank ran out in summer, staining the bathroom sink; the toxic scarlet of amanita muscaria against the ground. Strangely ecstasy-inducing when I was a child, each of these things, and now I think that’s because they signify mortality; even the red bore water, a sign of drought. On the second trip, Mike’s drone flew up in front of the car bonnet like a mechanical raptor, its camera-eye hungrily taking in the salt ponds, the pumps, and further away, the coast.

*

Thinking over these processes, the salt production and the production of Ana’s work, I think about dislocation. Perhaps this is where the grief comes in, an unshakeable sense I have of this work, I am a salt lake, as a kind of lament. What is it to be a salt lake? At Kapara te Hau it is to be involved in a relentless cycle of wet and dry, accretion and evaporation, staged and accelerated by human intervention. The harvesting is the taking-away or dislocation of minerals, for human consumption and use. But taking from where, or from whom?

It is hard to locate the salt’s point of origin, as a soluble material it partially evades this kind of locating or identification. Salt in the sea, or ocean salinity, is mainly caused by rain washing mineral ions from the land into water. Carbon dioxide in the air dissolves into rainwater, making it slightly acidic, so that when rain falls, it weathers the rocks, releasing mineral salts that separate into ions. At the same time, while all salt doesn’t directly come from the sea, at one point or another, all salt on the earth today was likely brought to its harvesting location by sea waters. So the salt lake at Kapara Te Hau holds sea water, but its intrinsic saltiness comes from the rocks on land and the gases in the air, and is in a constant transition form one state to the next. To be the ‘I’ of the salt lake is to be fugitive, to be changing form, and to experience dislocation as a constant.

When Ana’s work says, “I’m trying to connect across two islands and a strait”, I think of long skinny Aotearoa, and a line spanning Te Ika a Maui, crossing Te Moana o Raukawa, stretching down Te Waipounamu.3 I think about the way my own self sometimes feels physically held taut between places, from where I was born on the west coast in Te Ika a Maui, to Ōtautahi where I help install I am a salt lake in the gallery. I call Ana from there to ask: how about the sound? And realise that through the planning of the exhibition I've been thinking I will hear her voice when the work plays, reading or speaking the lines on the screen. Instead there is just the squeak of the artist’s fingers drawing lines on the wet windowpane, and a breathy rushing sound that is the movement of air at the ponds interacting with the video recorder.

Rather than explicitly locating themselves on the whenua, the work/the lake/the artist identifies an existence in relation to the voice itself when it says, “borders of the sea resonate within my body where the sounds live”. Although at the start of my conversations with Ana about this work I immediately tried to learn all I could about the geography of Kapara Te Hau, and about how salt is made there, slowly I have come to think that this work is not really about a single location. Rather, it is about bodies that harbour other bodies: sea water in the ponds, algae in the salty stagnant water, salt suspended in seawater in the deep ocean, the sound of Ana’s voice in her throat and chest, through cupped hands against the wind, or the beating heart in the ribcage of her body.

Each of the sites shown in the work—the salt ponds, the fogged-up window pane, the white screens with lines of text—could be seen as sites of crossing or transformation. That is, each are places where something substantial dissolves, or, where something materially insubstantial, such as an emotion or thought, is made legible as text or diagram. The philosopher Bergson has written about our human want for that which is identifiably solid as being linked to a desire for contact, even control: ‘Why do we think of a solid atom…? Because solids, being the bodies on which we clearly have most hold, are those which interest us most in our relations with the external world, and because contact is the only means which appears to be at our disposal in order to make our body act upon other bodies. But very simple experiments show that there is never true contact between two neighbouring bodies, and besides, solidity is far from being an absolutely defined state of matter.’4 Watching the work again, I think about this constant oscillation between feeling and telling, that which is tangible and that which is not: it is as if we want to put everything we see in our mouths, and then describe in words everything we taste. One form of narrative is not enough, every story is hungry for the next.

So this ‘I’ in the work. What if we see them as a plural form, as a kind of body within a body or bodies, and that interrelationship itself representing a grounding or location, a possible and yet fluid form of identity. Artist Lotus L. Kang has spoken of the parasite as one way of understanding such relationships between physical bodies, “The figure of the parasite is emblematic of a body in the world; there is no body without the detriment of another body. It’s an acknowledgement of the volatility of being a body. I’m interested instead in parasitical figures because they don’t deny a material reality, but embody instead an earthly insistence.”5

It is the ‘earthly insistence’ that lodges itself parasite-like in my own thinking when I read this, and when I go back to watch Ana’s work one more time, it’s still there. I am a salt lake presents a sometimes-oblique dialogue between self or selves and the environment, pushes at the edges of what is legible, or communicable, and at times retreats from visibility, behind a condensation-fogged window, or in the cloudiness of a saline solution. But through these transformations, a stubborn materiality remains. There’s no speaking about the concept or ideas in the work without referring to systems of weather and climate, industrial processes, digestion and preservation: Ana has made a work in which the kare-ā-roto, the inner working of the self,6 is inseparable from the earthy and tangible matter that surrounds us, and as such, the violence of mineral extraction, and the grief this incurs in relation to our own bodies—you cannot speak of one without the other, I cannot, we cannot. This is crying, this is a salt lake, this is the sea.

A tears analogy, reduced, could be a useful way to understand the process of salt production. It’s like the ponds used in the production of salt are eyes, excreting tears which ultimately dry as encrusted sodium chloride. The water at Kapara Te Hau actually comes from the sea, pumped into a series of distillation ponds so that the salt can be extracted from it. If you sit with it though, there’s a connection between these processes. That is, both involve the movement of water across a body, and a shift of physical state. Perhaps there is grief involved in both processes too. The extraction of salt from the sea, so that it can be harvested in its crystalline form: this embodies violence like any other mineral extraction. Salt is the easiest way to intensify the savouriness of food, to preserve, bind or emulsify. The salt harvest is perhaps slower and less visible than other forms of environmental extraction, still, the demand for the product is ceaseless, the process itself dramatically marking the land.

Similarly, the production of tears usually occurs at a moment of physical and psychological extremity, a bodily response inextricably connected with the inner self. A form of tangi or crying, as understood within te ao Māori, is articulated with precision in the whakataukī “Wahine tangi haehae, he ngaru moana, e kore e mātaki”. This is translated as “Wailing and laceration of women, mourning like a wave of the ocean, go on unceasingly”. The phrase is discussed by Leonie Pihama, Hineitimoana Greensill, Hōri Manuirirangi and Naomi Simmonds in their publication, He Kare-ā-Roto:

The ritual of mourning is a natural part of life and death in Te Ao Māori, with mediums such as waiata-tangi, apakura and mōteatea heavily laden with references to grief and loss. It was once common within Māori society for women to express this grief not only through wailing, but also the physical act of ‘haehae’, which involved the laceration of limbs, body parts and even the face with flakes of obsidian. This practice was custom following the loss of a loved one, and like the relentless tides of the ocean, women could be heard wailing during tangihanga whilst bearing the sacred wreathes of the pare kawakawa.1

Significantly, the tangi or crying, the voice itself, is positioned in relation to the ‘relentless tides’ of the sea, and in relation to other kinds of pain, some self-inflicted with shards of volcanic glass, obsidian. There is no separation here between the internal experience of grief and its physical embodiment. Further, in the reo Māori version at least, the word ‘like’ is not used: rather, the waves are the tangi. I think of my own mother, writing after dad’s death: “My heart is a stone that beats”. I understand now why she collected so many rocks around that time, weighing down all our windowsills.

*

The first trip to Kapara te Hau for filming was difficult. Ana described to me the harshness of the environment she met on arriving at the lakes from Blenheim. She stopped the car at the end of the road to the sea, got out, anxious maybe—because you never know if you’re going to get the footage that works, because your girlfriend is waiting in the car, and the camera gear is heavy. There, even the starchy sedge, hebe, pōheuheu that survive seem to cling onto the arid surface, wiry and matted. The light is white and the wind is strong, a prevailing northwesterly coursing down from Cook Strait and drying the area out.

It’s for these conditions that George Skellerup, founder of Para Rubber in Christchurch, in 1942 received government permission and began work to establish a solar salt-works there. Molten salt is used in the process of recycling old rubber; by 1955 Dominion Salt Limited was harvesting 3,000 tonnes of salt each year. Today, salt from these ponds accounts for about half of New Zealand’s salt consumption. Rubber production itself is a violent process: harvested as liquid latex from the para tree, before being acidified, dried, smoked, and accounting for mass deforestation to enable rubber plantations.2 The salt is what enables the next phase in the ‘life-cycle’ of natural rubber, under conditions of extreme heat.

A second trip, in late summer when the salt ponds bloom blood-red with microscopic algae, was easier. Using a drone, Ana and videographer Mike Pointon filmed over three days, recording the area in another season or phase in the cycle of salt production. From above, the ponds look meaty, a carefully regulated series of open wounds in the landscape. Too easy maybe to use these metaphors, after all, all bodies leak, sweat, bleed, excrete. Too easy to think of the expressions ‘rubbing salt in the wounds’ or ‘salt of the earth’, both of which evidence the historical value of salt as an anti-bacterial, and as a necessity. In Kapara te Hau it is the algae, stressed by the increasing salinity, that produces the red as the water evaporates.

Recently I've been thinking about these reds in nature, and their role as an alert or rupture of some kind. The stain of blood on my dad’s shirt as he walked out of the bush on Karioi carrying a dead goat; the bright rust colour of the water that came up from a bore in the ground when our rainwater tank ran out in summer, staining the bathroom sink; the toxic scarlet of amanita muscaria against the ground. Strangely ecstasy-inducing when I was a child, each of these things, and now I think that’s because they signify mortality; even the red bore water, a sign of drought. On the second trip, Mike’s drone flew up in front of the car bonnet like a mechanical raptor, its camera-eye hungrily taking in the salt ponds, the pumps, and further away, the coast.

*

Thinking over these processes, the salt production and the production of Ana’s work, I think about dislocation. Perhaps this is where the grief comes in, an unshakeable sense I have of this work, I am a salt lake, as a kind of lament. What is it to be a salt lake? At Kapara te Hau it is to be involved in a relentless cycle of wet and dry, accretion and evaporation, staged and accelerated by human intervention. The harvesting is the taking-away or dislocation of minerals, for human consumption and use. But taking from where, or from whom?

It is hard to locate the salt’s point of origin, as a soluble material it partially evades this kind of locating or identification. Salt in the sea, or ocean salinity, is mainly caused by rain washing mineral ions from the land into water. Carbon dioxide in the air dissolves into rainwater, making it slightly acidic, so that when rain falls, it weathers the rocks, releasing mineral salts that separate into ions. At the same time, while all salt doesn’t directly come from the sea, at one point or another, all salt on the earth today was likely brought to its harvesting location by sea waters. So the salt lake at Kapara Te Hau holds sea water, but its intrinsic saltiness comes from the rocks on land and the gases in the air, and is in a constant transition form one state to the next. To be the ‘I’ of the salt lake is to be fugitive, to be changing form, and to experience dislocation as a constant.

When Ana’s work says, “I’m trying to connect across two islands and a strait”, I think of long skinny Aotearoa, and a line spanning Te Ika a Maui, crossing Te Moana o Raukawa, stretching down Te Waipounamu.3 I think about the way my own self sometimes feels physically held taut between places, from where I was born on the west coast in Te Ika a Maui, to Ōtautahi where I help install I am a salt lake in the gallery. I call Ana from there to ask: how about the sound? And realise that through the planning of the exhibition I've been thinking I will hear her voice when the work plays, reading or speaking the lines on the screen. Instead there is just the squeak of the artist’s fingers drawing lines on the wet windowpane, and a breathy rushing sound that is the movement of air at the ponds interacting with the video recorder.

Rather than explicitly locating themselves on the whenua, the work/the lake/the artist identifies an existence in relation to the voice itself when it says, “borders of the sea resonate within my body where the sounds live”. Although at the start of my conversations with Ana about this work I immediately tried to learn all I could about the geography of Kapara Te Hau, and about how salt is made there, slowly I have come to think that this work is not really about a single location. Rather, it is about bodies that harbour other bodies: sea water in the ponds, algae in the salty stagnant water, salt suspended in seawater in the deep ocean, the sound of Ana’s voice in her throat and chest, through cupped hands against the wind, or the beating heart in the ribcage of her body.

Each of the sites shown in the work—the salt ponds, the fogged-up window pane, the white screens with lines of text—could be seen as sites of crossing or transformation. That is, each are places where something substantial dissolves, or, where something materially insubstantial, such as an emotion or thought, is made legible as text or diagram. The philosopher Bergson has written about our human want for that which is identifiably solid as being linked to a desire for contact, even control: ‘Why do we think of a solid atom…? Because solids, being the bodies on which we clearly have most hold, are those which interest us most in our relations with the external world, and because contact is the only means which appears to be at our disposal in order to make our body act upon other bodies. But very simple experiments show that there is never true contact between two neighbouring bodies, and besides, solidity is far from being an absolutely defined state of matter.’4 Watching the work again, I think about this constant oscillation between feeling and telling, that which is tangible and that which is not: it is as if we want to put everything we see in our mouths, and then describe in words everything we taste. One form of narrative is not enough, every story is hungry for the next.

So this ‘I’ in the work. What if we see them as a plural form, as a kind of body within a body or bodies, and that interrelationship itself representing a grounding or location, a possible and yet fluid form of identity. Artist Lotus L. Kang has spoken of the parasite as one way of understanding such relationships between physical bodies, “The figure of the parasite is emblematic of a body in the world; there is no body without the detriment of another body. It’s an acknowledgement of the volatility of being a body. I’m interested instead in parasitical figures because they don’t deny a material reality, but embody instead an earthly insistence.”5

It is the ‘earthly insistence’ that lodges itself parasite-like in my own thinking when I read this, and when I go back to watch Ana’s work one more time, it’s still there. I am a salt lake presents a sometimes-oblique dialogue between self or selves and the environment, pushes at the edges of what is legible, or communicable, and at times retreats from visibility, behind a condensation-fogged window, or in the cloudiness of a saline solution. But through these transformations, a stubborn materiality remains. There’s no speaking about the concept or ideas in the work without referring to systems of weather and climate, industrial processes, digestion and preservation: Ana has made a work in which the kare-ā-roto, the inner working of the self,6 is inseparable from the earthy and tangible matter that surrounds us, and as such, the violence of mineral extraction, and the grief this incurs in relation to our own bodies—you cannot speak of one without the other, I cannot, we cannot. This is crying, this is a salt lake, this is the sea.

Written on the occasion of Ana Iti’s exhibition I am a salt lake at The Physics Room, Ōtautahi, 9 September - 22 October 2023.

[1] Leonie Pihama, Hineitimoana Greensill, Hōri Manuirirangi and Naomi Simmonds (Eds.), He Kare-ā-Roto: A Selection of Whakataukī related to Māori Emotions (Hamilton, Aotearoa: Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019), 19-20.

[2] This is how natural rubber is made, the kind used by Skellerup. Making synthetic rubber begins with a base of petrochemicals. Silicone rubber starts with massive quantities of quartz sand.

[3] Recently, when I think of the north I think of a work of Ana’s in progress, which focuses on a wharf in Rawene, in the Hokianga where her dad’s side of the family is from. The wharf stands in another salty body of water, this one punctuated by mangroves which make gobstopper sounds, like small mouths in the mud as the tide recedes.

[2] This is how natural rubber is made, the kind used by Skellerup. Making synthetic rubber begins with a base of petrochemicals. Silicone rubber starts with massive quantities of quartz sand.

[3] Recently, when I think of the north I think of a work of Ana’s in progress, which focuses on a wharf in Rawene, in the Hokianga where her dad’s side of the family is from. The wharf stands in another salty body of water, this one punctuated by mangroves which make gobstopper sounds, like small mouths in the mud as the tide recedes.

[4] Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory, transl. by Nancy Margaret Paul and W. Scott Palmer (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1911): 232-298., 263.

[5] Lotus L. Kang in conversation with Chloe Ting, ‘Working with the lack’, Afterall, Summer-Autumn 23, Iss. 55/56, 105.

[6] While kare is most frequently translated as a verb, ‘to long for, desire ardently’, Te Aka includes an additional translation as a noun, ‘ripple, surface (of the sea)’, and in relation to pōkarekare: ‘to be agitated (as a liquid), to be stirred up’. See Te Aka Māori Dictionary entry.

[5] Lotus L. Kang in conversation with Chloe Ting, ‘Working with the lack’, Afterall, Summer-Autumn 23, Iss. 55/56, 105.

[6] While kare is most frequently translated as a verb, ‘to long for, desire ardently’, Te Aka includes an additional translation as a noun, ‘ripple, surface (of the sea)’, and in relation to pōkarekare: ‘to be agitated (as a liquid), to be stirred up’. See Te Aka Māori Dictionary entry.