The polypod does not sit still

The polypod has

many feet or legs.

The polypod is herbivorous, short-bodied, and antenniferous.

The polypod has a body like a broadbean pod, many-waisted.

It has not occurred to many people to ask if a polypod gets lonely, depressed, or is dangerous.

The polypod has a bitter-sweet taste and is among few ferns used in cooking, for example as a spice for nougat.

The Polypod 200 is available on prescription.

Some people say the Polypod 200 has been effective in the treatment of infections of the lungs, urinary tract, ear, sinus, throat, and skin.

The internet knows about the polypod. I’ve searched on many consecutive days now, compiling what arrives in response to various questions: What is a polypod? How do I identify a polypod? How do polypods communicate? What is more difficult is bringing all the information together in a way that offers a coherent image, able to be visualised. I search and read while the light goes down outside and after a while I become only eyes, blinking like phone cameras. Later, I become only hands, picking up and putting down books about mushrooms and insects and birds, searching for a form appropriate to the word, thing, or being which gives this exhibition its title.

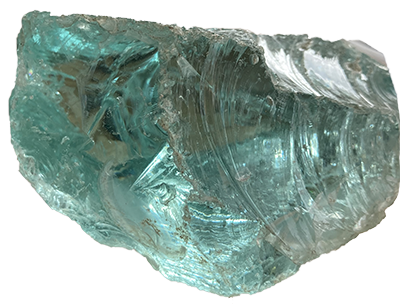

After talking to Nicola and Jack about it, and then this every day googling, I start to think about the herb-eating many-legged antenna-crowned medicinal polypod, not as something able to be seen, but as something formed through movement or momentum. The idea I have is less of a solid or unified thing, more like a series of parts—chopped vegetables, pills, limbs, plastics, crystals and pieces of coloured glass—flying through space or a blender, coming together kaleidoscopically, and then dispersing again. The polypod as that which coalesces through energetic force, that which sticks or clumps or clots, momentarily.

This offers a way to think about Jack and Nicola’s new works too: the works as temporary collectives, made up of components or parts in motion. With Jack’s works, modular lamps and stools, it is possible to make the connection in a literal way: the multiple elements that make up this ‘furniture system’ (FS) can be mixed and remixed to assemble a whole. Powder coated, Endeavor, Ghost, Shweppes, Shotover, their colours’ names register a local vernacular. The lamps have frosted sconces, also interchangeable. In one possible configuration, the stools are on wheels, and one imagines that they could or would move about of their own volition, monofunctional robots whose purpose is to fill the room with a sense of ease and gentle activity. Vinyl gym mats serve as seat cushions on the stools; you can’t look at them and not feel your high school thighs, sticking with sweat as you sit in PE. I remember how hard it was to sit still at that time in my life, how hard to move in case of being noticed, and how sport felt the safest place for bodies to move without everything flying out of the correct order. I remember what the gym smelled like in assembly and that it had huge non-transparent windows high up, gridded with thin black lines like maths paper. Jack’s works are made to move; there’s an implicit suggestion that they might roll and unroll across the polished concrete floor of the gallery.

Nicola’s paintings appear initially to be more fixed, according to their media: oil paint, stretched canvas, sometimes with thick paper clay wafers balanced on top of the paintings. Yet as compositions they suggest a more in-process or open view of things. In three of the works, Feelings, Bell and Envoy, a circle loosely contains what appears to be organic material—something like fruit flesh inside of a skin—while shards or peels or petals are radiated or emitted from this. Perhaps we look down on a bisected globe, a melon on a plate. In a fourth work, Pumice, the perspective is different, like looking at the side of a drinking glass or jar from which many legs, many feet, or many antennae, unfurl. Across the works there is a sense that what we are seeing is paused, poised, that processes including the release of odour, decomposition, germination, or desiccation, continue to occur.

Within a system of perpetual motion, the work of the artist might be conceived as gathering, sorting, holding, or shouldering ideas. Reading Ursula K. Le Guin’s ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’ essay I am struck again by her idea of a story as a bag, a holder of things and meanings.[1] She draws out the metaphor of a story as a bag or container, via Elizabeth Fisher’s earlier assertion that rather than the spear of metal tool, “The first cultural device was a recipient.”[2] Le Guin’s analogy is baggy too, in it there is space for not only fiction as a form of holding things together, toting them about to show each other, but for contemporary practices like these ones in Polypod. That is, for the idea that the temporary gathering of images and material is a primary act of human generosity, generating narrative, in Le Guin’s words, “a way of trying to describe…what people actually do and feel, how people relate to everything else in this vast sack, this belly of the universe, this womb of things to be and tomb of things that were, this unending story.”

It feels like a grand note to end things on, too grand. Better we return to the polypod, this time a staghorn fern growing in my living room, from a rhizome in the genus polypodium, family polypodiaceae. Its name comes from the Greek, ‘many little feet’, accounting for the foot-like appearance of its root. This one I have looks top-heavy and unstable, it’s an epiphyte and likely wants the anchor of a tree trunk rather than a pot. Its green antler-branches quiver slightly in the breath of the heat pump. It is only here in this particular form for now, for a bit.

People say that the polypod has never been seen, or that it is an envoy or a bell.

The polypod has a Libra sun, a Libra moon, its anatomical link is to the kidney, and its crystal is rose quartz.

The polypod is a plant, an algae, or it is an insect and it eats other insects.

The polypod does not sit still.

Written for Nicola Farquhar and Jack Hadley, Polypody, Laree Payne Gallery, Kirikiriroa Hamilton, 27 September - 21 October 2023.

The polypod is herbivorous, short-bodied, and antenniferous.

The polypod has a body like a broadbean pod, many-waisted.

It has not occurred to many people to ask if a polypod gets lonely, depressed, or is dangerous.

The polypod has a bitter-sweet taste and is among few ferns used in cooking, for example as a spice for nougat.

The Polypod 200 is available on prescription.

Some people say the Polypod 200 has been effective in the treatment of infections of the lungs, urinary tract, ear, sinus, throat, and skin.

The internet knows about the polypod. I’ve searched on many consecutive days now, compiling what arrives in response to various questions: What is a polypod? How do I identify a polypod? How do polypods communicate? What is more difficult is bringing all the information together in a way that offers a coherent image, able to be visualised. I search and read while the light goes down outside and after a while I become only eyes, blinking like phone cameras. Later, I become only hands, picking up and putting down books about mushrooms and insects and birds, searching for a form appropriate to the word, thing, or being which gives this exhibition its title.

After talking to Nicola and Jack about it, and then this every day googling, I start to think about the herb-eating many-legged antenna-crowned medicinal polypod, not as something able to be seen, but as something formed through movement or momentum. The idea I have is less of a solid or unified thing, more like a series of parts—chopped vegetables, pills, limbs, plastics, crystals and pieces of coloured glass—flying through space or a blender, coming together kaleidoscopically, and then dispersing again. The polypod as that which coalesces through energetic force, that which sticks or clumps or clots, momentarily.

This offers a way to think about Jack and Nicola’s new works too: the works as temporary collectives, made up of components or parts in motion. With Jack’s works, modular lamps and stools, it is possible to make the connection in a literal way: the multiple elements that make up this ‘furniture system’ (FS) can be mixed and remixed to assemble a whole. Powder coated, Endeavor, Ghost, Shweppes, Shotover, their colours’ names register a local vernacular. The lamps have frosted sconces, also interchangeable. In one possible configuration, the stools are on wheels, and one imagines that they could or would move about of their own volition, monofunctional robots whose purpose is to fill the room with a sense of ease and gentle activity. Vinyl gym mats serve as seat cushions on the stools; you can’t look at them and not feel your high school thighs, sticking with sweat as you sit in PE. I remember how hard it was to sit still at that time in my life, how hard to move in case of being noticed, and how sport felt the safest place for bodies to move without everything flying out of the correct order. I remember what the gym smelled like in assembly and that it had huge non-transparent windows high up, gridded with thin black lines like maths paper. Jack’s works are made to move; there’s an implicit suggestion that they might roll and unroll across the polished concrete floor of the gallery.

Nicola’s paintings appear initially to be more fixed, according to their media: oil paint, stretched canvas, sometimes with thick paper clay wafers balanced on top of the paintings. Yet as compositions they suggest a more in-process or open view of things. In three of the works, Feelings, Bell and Envoy, a circle loosely contains what appears to be organic material—something like fruit flesh inside of a skin—while shards or peels or petals are radiated or emitted from this. Perhaps we look down on a bisected globe, a melon on a plate. In a fourth work, Pumice, the perspective is different, like looking at the side of a drinking glass or jar from which many legs, many feet, or many antennae, unfurl. Across the works there is a sense that what we are seeing is paused, poised, that processes including the release of odour, decomposition, germination, or desiccation, continue to occur.

Within a system of perpetual motion, the work of the artist might be conceived as gathering, sorting, holding, or shouldering ideas. Reading Ursula K. Le Guin’s ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’ essay I am struck again by her idea of a story as a bag, a holder of things and meanings.[1] She draws out the metaphor of a story as a bag or container, via Elizabeth Fisher’s earlier assertion that rather than the spear of metal tool, “The first cultural device was a recipient.”[2] Le Guin’s analogy is baggy too, in it there is space for not only fiction as a form of holding things together, toting them about to show each other, but for contemporary practices like these ones in Polypod. That is, for the idea that the temporary gathering of images and material is a primary act of human generosity, generating narrative, in Le Guin’s words, “a way of trying to describe…what people actually do and feel, how people relate to everything else in this vast sack, this belly of the universe, this womb of things to be and tomb of things that were, this unending story.”

It feels like a grand note to end things on, too grand. Better we return to the polypod, this time a staghorn fern growing in my living room, from a rhizome in the genus polypodium, family polypodiaceae. Its name comes from the Greek, ‘many little feet’, accounting for the foot-like appearance of its root. This one I have looks top-heavy and unstable, it’s an epiphyte and likely wants the anchor of a tree trunk rather than a pot. Its green antler-branches quiver slightly in the breath of the heat pump. It is only here in this particular form for now, for a bit.

People say that the polypod has never been seen, or that it is an envoy or a bell.

The polypod has a Libra sun, a Libra moon, its anatomical link is to the kidney, and its crystal is rose quartz.

The polypod is a plant, an algae, or it is an insect and it eats other insects.

The polypod does not sit still.

Written for Nicola Farquhar and Jack Hadley, Polypody, Laree Payne Gallery, Kirikiriroa Hamilton, 27 September - 21 October 2023.