The finest powder in the

largest quantities

A graining, a sanding.

The finest powder in the largest quantities.

[…] the sound of sand dunes

shifting

without

wind.[1]

For a couple of months now I’ve been polishing the black ceramic cooktop, every day almost. If you use a really fine weave fabric – a piece of t-shirt is good – really lean into it, just a bit of the chalk-pink cleaner, you can achieve a smelted black gleam like nothing else. When it’s done I can concentrate more clearly, relieved that this jet black glass was there all the time, intact under the dried cooking spills. At first I was worried it would not be; some surfaces you have to live with for a while to know they are going to be okay, can bear heat and wet without shrinking or fading, melting or scarring.

There might be a kind of deep assurance that comes with living next to a huge body of water, a lake that freezes to a stone in winter. I’m not sure, but if there is I think that it would be like the feeling of this jet black cooktop square when it’s done.

The finest powder in the largest quantities.

[…] the sound of sand dunes

shifting

without

wind.[1]

For a couple of months now I’ve been polishing the black ceramic cooktop, every day almost. If you use a really fine weave fabric – a piece of t-shirt is good – really lean into it, just a bit of the chalk-pink cleaner, you can achieve a smelted black gleam like nothing else. When it’s done I can concentrate more clearly, relieved that this jet black glass was there all the time, intact under the dried cooking spills. At first I was worried it would not be; some surfaces you have to live with for a while to know they are going to be okay, can bear heat and wet without shrinking or fading, melting or scarring.

There might be a kind of deep assurance that comes with living next to a huge body of water, a lake that freezes to a stone in winter. I’m not sure, but if there is I think that it would be like the feeling of this jet black cooktop square when it’s done.

The exhibition title is Superstimulus. There are two common examples the

internet uses to illustrate the term. One is a chocolate bar, a concentrated version

of stimuli – sugar, salt and fat – to which humans are already drawn. The other

is a bird, which shows a preference for an egg that is larger than its own,

even though that egg might be plastic, or cold. I wonder who comes up with an

experiment like that, and then think about the egg – either egg really. It’s a

good example for superstimilus, you can see it clearly as a diagram, but always

I get distracted by the bird, caught in the weight of its decision. Lyn

Hejinian writes, “Each moment stands under an enormous vertical and horizontal

pressure of information, potent with ambiguity, meaning-full, unfixed, and

certainly incomplete.”[4] Hejinian

notes language is a condition we inhabit; it never rests. But this is better

said by her direct, for a minute we can even lean on it maybe, held, and then woken:

in a great lock of letters

like knock look . . .[5]

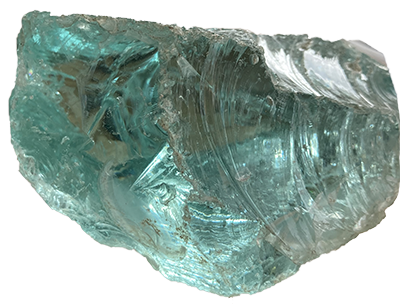

I have too many tabs open about glass making, about silica

and soda ash: ‘soda-silica-lime-glass’, a name like biting into something cold and minty and perfect. One glass polishing day I drive home listening to the story of Poutini and Waitaiki and the obsidian deposit at Tūhua Island, kiripaka (flint) at Waiapu, ōnewa (basalt) at Opito Bay[6], glass green tangiwai (bowenite) in Piopiotahi, matā (lava) hitting the water at Whangamatā. Everywhere there is glass and rock, bodies of sea water.

All these things are going to be okay I think, and today it is the only thing that brings relief. They will outlast our bodies, along with windshields and the shells of electronic things, headphones shaped to fit in our earlobes and encircle our heads, elastic bandage fabric that was designed to stretch and to hold broken limbs, USB ports and synthetic bra straps and the eerily lit email on your screen. Thinking this is like becoming extremely old very quickly, feeling that your skin is younger than you are, but it will pass.

Now it’s December and there are New Zealand oranges as big as your outstretched hand at Lim Chhour, some of the best I’ve ever tasted. I eat two in one sitting, feeling like I sink into each mouthful, or maybe it almost submerges me. I stop polishing the cooktop every day and it’s fine. Sometimes there are things spilled on top of each other and it’s even fine then. The finest powder in the largest quantities, the sand and the glass, and all the tides that brought them here.

This essay was written for Superstimulus: Wendelien Bakker, Teghan Burt, Wai Ching Chan, Kah Bee Chow, Carrie Cook, Nicola Farquhar, Anna Sew Hoy, curated by Nicola Farquhar, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2019.

in a great lock of letters

like knock look . . .[5]

I have too many tabs open about glass making, about silica

and soda ash: ‘soda-silica-lime-glass’, a name like biting into something cold and minty and perfect. One glass polishing day I drive home listening to the story of Poutini and Waitaiki and the obsidian deposit at Tūhua Island, kiripaka (flint) at Waiapu, ōnewa (basalt) at Opito Bay[6], glass green tangiwai (bowenite) in Piopiotahi, matā (lava) hitting the water at Whangamatā. Everywhere there is glass and rock, bodies of sea water.

All these things are going to be okay I think, and today it is the only thing that brings relief. They will outlast our bodies, along with windshields and the shells of electronic things, headphones shaped to fit in our earlobes and encircle our heads, elastic bandage fabric that was designed to stretch and to hold broken limbs, USB ports and synthetic bra straps and the eerily lit email on your screen. Thinking this is like becoming extremely old very quickly, feeling that your skin is younger than you are, but it will pass.

Now it’s December and there are New Zealand oranges as big as your outstretched hand at Lim Chhour, some of the best I’ve ever tasted. I eat two in one sitting, feeling like I sink into each mouthful, or maybe it almost submerges me. I stop polishing the cooktop every day and it’s fine. Sometimes there are things spilled on top of each other and it’s even fine then. The finest powder in the largest quantities, the sand and the glass, and all the tides that brought them here.

This essay was written for Superstimulus: Wendelien Bakker, Teghan Burt, Wai Ching Chan, Kah Bee Chow, Carrie Cook, Nicola Farquhar, Anna Sew Hoy, curated by Nicola Farquhar, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2019.

[1]Cassandra Barnett, from ‘Listen your way home’, published in ATE: Journal of Māori Art, editors Bridget Rewiti and Matariki Wilson (Wellington, 2019).

[2] Anne Carson, Glass Irony and God (NY: New Directions, 1995).

[3] Hera Lindsay Bird, ‘Staffroom grafitti when i’m tired’, Ultra Vires: Totally dark in ten or twelve different ways, lightreading (8fold: Munich, 2016).