The end of the sea

16 York Place

Edinburgh

EH1 3EP

05 November

Edinburgh

EH1 3EP

05 November

RE: The end of the sea.

Dear Editor,

Recently I have been worrying about the sea. It’s not the sea I left last summer in Wellington harbour, a living swell which glinted and heaved at the end of the runway as we took off. It’s looking grey from my third floor window, York Place, Edinburgh; it’s looking solid, still, far away. It seems to have faded, its colour that of a HB pencil, erased. Its symptoms suggest an illness, or extreme old age.

In the paper I read often about the sickness of the sea, about it getting warmer, soaking in toxins, and its great shields of arctic ice sloughing off and dissolving like sugary confections. Each day I count the oil tankers out there, pausing on their way across the North Sea, red and square like paperweights on an unstable horizon. They sit as if they are waiting for something. I wonder if they too know the sea is running out of time. I have been recording its states, trying to make sense of it.

A paper sea. Some days it looks as if the whole thing might crumple up like so much cheap creased paper, foil-backed, and who would smooth it again, with patience and the back of a teaspoon? After one hot day a dense fog rolls in from the coast, damply cloaking and then blinding the city, and the bus driver tell us it’s a har, and then laughs: New Zealanders cannot say the word. Watching the har approach, the sea transformed into paper whiteness, it’s Wittgenstein you think of, dying obsessed by the impossibility of imagining a transparent white. If he could see this: a white just perceptibly undermined by the awareness of the sea beneath its surface. You think of John Cage, building a 4’33” minute emptiness for the silence to make itself heard. You can’t hear the sea in a thick har.

A photographed sea. The framed photograph my window makes of the sea, served up in squares of light and dark, over exposed, salt fixed. It’s all the photographs I have ever seen of the sea: Hiroshi Sugimoto’s seascapes, Catherine Opie’s surfers, and all the postcards. It’s flat and I would pin it to my wall if I couldn’t look out the window each day and see it there, pinned to the horizon already.

A sea all surface. I have been watching that surface, thinking that it is like an opaque skin. It is the biggest minimalist canvas, 139,668,500 square miles of same and same and same. You look, and think of Picasso saying ‘a painting is the sum of its destructions’: it’s that kind of surface on this sea, one which has swallowed all the others. Contained within that perfect and constant line, the horizon, it is the end of all lines, permanent marks. It is all edges at once, and no edges at all.

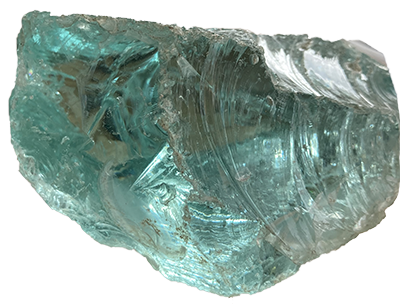

A solid sea. The world’s biggest solid sculpture, a mass beyond measurement. And containing within it the potential for other solids: oxygen and water, silicon and salt, iron sands, oil, magnesium and calcium. And holding all things dropped: buoyant things on the surface; less buoyant things suspended in water; dead, saturated, heavy weighted things foundered deep at the bottom. A solid sea, and full of weights to keep it in place.

An expanding sea, bloating and dying. Reading, intermittently, the story of a sculpture being made back in New Zealand, Taranaki —70 litres of used fuel oil converted to cement and cast—I realise immediately it is a monument to the passing of the sea, a solid monument to mark a time when the sea was younger, and before its age bean to show. February 2013, the cement sculpture will go down like a stone, plunging silent to the deep end of our unknown, the end of comprehension and sight, and sit there until the end of the sea.

Yours sincerely,

Abby Cunnane

This letter was written in 2013 for Maddie Leach, If you find the good oil let us know, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery.