Lichen like light

While Emma and I spoke on the phone about

lichen and her new work I washed all my smaller rocks, bullet-sized to biscuit-sized.

I’ve had rocks on the windowsill as far back as I can remember. At some point I

stopped bringing them home, but by that time people—mainly my mum—had started

to bring me small rocks that they found too, and I’d guiltily add them to the sill.

I remember where almost all of the rocks are from, and in recent years I’ve

started furtively returning them, like overdue library books. Meantime I run

them under the tap often, mostly when I’m on the phone, because of the way most

rocks’ colour deepens in the wet. When you see that wet colour, it’s like simultaneously

recognising that they were thirsty, and that you are, too.

The new works too have this quality of thirst. In the making process they are saturated with a flashe and acrylic solution; more of this wet pigment is added as they sit on the wall, before they can dry out. The weight of the solution remains in the finished work, a cloudy matte heaviness in the now-dry canvas. There’s a word used to describe lichen, ‘crustose,’[1] which comes into my mind—it’s precisely what it sounds like. I was already thinking about lichen a lot before I saw this work, but the word belongs here too. The paintings wear crustose easily, like you might wear a shirt.

There have been many garments in Emma’s work over the years, and it’s comfortable for me to locate this idea again, to find the seams in this work and connect them with the structure of a woman’s oversize shirt, with the utility and intimacy of work clothes in which one can move. There are even diamond seams in some of the smaller works, making me image search Agnes Martin’s quilted painting suit again, drawing my eyes to the crease in my own sleeve. I rest for a minute on the diamond-crossed works, like Study of a Square and Lichen (2020), on the satisfying weight of them on the wall, the weight of a sleeve on an arm.

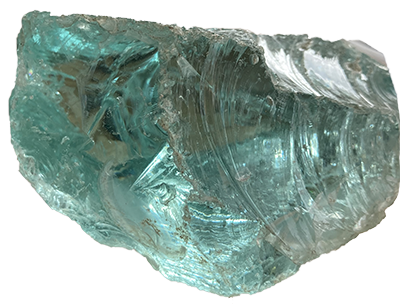

But it’s the lichen I want to stay with. The lichen, because of the crater line along the Port Hills, Ngā Kōhatu Whakarekareka o Tamatea Pōkai Whenua,[2] where Emma was walking as we spoke recently and where the large unstretched canvases sit in some of her photographs: Being East / Crater Rim (2020) and Being West / Crater Rim (2020). Lichens are what the bone-hard rock shoulders up there wear—or, they wear each other, the microorganism and the terrain, who is to say?[3]It’s not a line I have any interest in drawing; surely you too have had a shirt so old and soft that you don’t know where your skin ends and the fabric begins? The lichen may be wearing the rocks, the rocks wearing the light, which is in turn held close by the photosynthetic lichen. As I picture it now, along the crater the light is sodden with rain, a colour like that of oxidised copper on your wrist. Certainly, the rain is what brings everything into focus.

Aotearoa is host to about 2000 types of lichen (up to 40% endemic[4]). An online inventory allows you to identify and locate these under titles such as ‘Arctic frosted rock tripe’, ‘Mealy pixie cup’, ‘Fluffy dust’, ‘Candleflame’ and ‘Cartilage’, ‘Porridge lichen’.[5] Lichens are not plants as such, but composites of two or more microorganisms—a fungi and an algae—that co-exist. The fungi and the algae’s needs correspond: “The fungi do not pass any nutrients back to the algae, but in return for ‘milking’ them of carbohydrates they produce, the fungi protect the algal cells from mechanical damage and excessive sunlight and keep them moist.”[6] New Zealand Geographic’s Derek Grzelewski notes, “In strong sunlight, the surface of lichens often appears drab, matt and opaque, but that’s just the fungi protecting their algal garden from excessive exposure to sunlight. When moistened by rain, dew or fog, the lichens’ surfaces become translucent, allowing the sunlight through and turning on photosynthetic processes.”[7]

Some lichens contain fluorescence, visible to human eyes under UV light, as a by-product of their growing processes. Some of Emma’s larger works, like Boxy / Bias (2020) suggest this property, an acidic luminosity in tone. The paler lichen-like works, less so, but I suspect there is a low-lit day up there on the hill in which they would. I don’t know what would happen if these canvases were let to soak in the rain, if the pigment would become soluable again, if they would fold under their own wet-weight, and emit light.

Lichen has always seemed dry to me—I remember it starchy on the fence posts, the metal gate-locks on the farm—but the more I learn about it, the more I recognise its multiple relationships to water. Climatologists use the pace of lichen’s appearance on rocks recently exposed by melting glaciers to measure rates of global warming.[8] They survive equally well in the dry; in 2005 two species of lichen were launched into space, taken out of the capsule and exposed to zero temperature and the spectrum of ultraviolet light for 15 days. On return to Earth there was no discernible change in the lichens.[9] After we talk about Emma’s work, I read more, and soon lichen is drinking up pavements, trees, drinking up pages of the internet as I scroll in bed at night with the brightness turned down.

I saw the Port Hills properly for the first time when I was in Ōtautahi for a few hot weeks in February 2017. Emma and Tessa and Mel took me to Rāpaki and we swam the deep wide dark swim out to the buoy. We lay looking back and up towards the hills above Lyttleton Harbour, Whakaraupō, which from that perspective appear to be propping up the sky. It’s so much later that this work happens, I’d almost forgotten that swim. Looking at the work now though, in wet August, and thinking about the slow tides of lichen growing over the rocks, I remember it with physical clarity. I know we would have talked about clothes, about summer things like towels as we dried, salty, back on the beach.

The new works too have this quality of thirst. In the making process they are saturated with a flashe and acrylic solution; more of this wet pigment is added as they sit on the wall, before they can dry out. The weight of the solution remains in the finished work, a cloudy matte heaviness in the now-dry canvas. There’s a word used to describe lichen, ‘crustose,’[1] which comes into my mind—it’s precisely what it sounds like. I was already thinking about lichen a lot before I saw this work, but the word belongs here too. The paintings wear crustose easily, like you might wear a shirt.

There have been many garments in Emma’s work over the years, and it’s comfortable for me to locate this idea again, to find the seams in this work and connect them with the structure of a woman’s oversize shirt, with the utility and intimacy of work clothes in which one can move. There are even diamond seams in some of the smaller works, making me image search Agnes Martin’s quilted painting suit again, drawing my eyes to the crease in my own sleeve. I rest for a minute on the diamond-crossed works, like Study of a Square and Lichen (2020), on the satisfying weight of them on the wall, the weight of a sleeve on an arm.

But it’s the lichen I want to stay with. The lichen, because of the crater line along the Port Hills, Ngā Kōhatu Whakarekareka o Tamatea Pōkai Whenua,[2] where Emma was walking as we spoke recently and where the large unstretched canvases sit in some of her photographs: Being East / Crater Rim (2020) and Being West / Crater Rim (2020). Lichens are what the bone-hard rock shoulders up there wear—or, they wear each other, the microorganism and the terrain, who is to say?[3]It’s not a line I have any interest in drawing; surely you too have had a shirt so old and soft that you don’t know where your skin ends and the fabric begins? The lichen may be wearing the rocks, the rocks wearing the light, which is in turn held close by the photosynthetic lichen. As I picture it now, along the crater the light is sodden with rain, a colour like that of oxidised copper on your wrist. Certainly, the rain is what brings everything into focus.

Aotearoa is host to about 2000 types of lichen (up to 40% endemic[4]). An online inventory allows you to identify and locate these under titles such as ‘Arctic frosted rock tripe’, ‘Mealy pixie cup’, ‘Fluffy dust’, ‘Candleflame’ and ‘Cartilage’, ‘Porridge lichen’.[5] Lichens are not plants as such, but composites of two or more microorganisms—a fungi and an algae—that co-exist. The fungi and the algae’s needs correspond: “The fungi do not pass any nutrients back to the algae, but in return for ‘milking’ them of carbohydrates they produce, the fungi protect the algal cells from mechanical damage and excessive sunlight and keep them moist.”[6] New Zealand Geographic’s Derek Grzelewski notes, “In strong sunlight, the surface of lichens often appears drab, matt and opaque, but that’s just the fungi protecting their algal garden from excessive exposure to sunlight. When moistened by rain, dew or fog, the lichens’ surfaces become translucent, allowing the sunlight through and turning on photosynthetic processes.”[7]

Some lichens contain fluorescence, visible to human eyes under UV light, as a by-product of their growing processes. Some of Emma’s larger works, like Boxy / Bias (2020) suggest this property, an acidic luminosity in tone. The paler lichen-like works, less so, but I suspect there is a low-lit day up there on the hill in which they would. I don’t know what would happen if these canvases were let to soak in the rain, if the pigment would become soluable again, if they would fold under their own wet-weight, and emit light.

Lichen has always seemed dry to me—I remember it starchy on the fence posts, the metal gate-locks on the farm—but the more I learn about it, the more I recognise its multiple relationships to water. Climatologists use the pace of lichen’s appearance on rocks recently exposed by melting glaciers to measure rates of global warming.[8] They survive equally well in the dry; in 2005 two species of lichen were launched into space, taken out of the capsule and exposed to zero temperature and the spectrum of ultraviolet light for 15 days. On return to Earth there was no discernible change in the lichens.[9] After we talk about Emma’s work, I read more, and soon lichen is drinking up pavements, trees, drinking up pages of the internet as I scroll in bed at night with the brightness turned down.

I saw the Port Hills properly for the first time when I was in Ōtautahi for a few hot weeks in February 2017. Emma and Tessa and Mel took me to Rāpaki and we swam the deep wide dark swim out to the buoy. We lay looking back and up towards the hills above Lyttleton Harbour, Whakaraupō, which from that perspective appear to be propping up the sky. It’s so much later that this work happens, I’d almost forgotten that swim. Looking at the work now though, in wet August, and thinking about the slow tides of lichen growing over the rocks, I remember it with physical clarity. I know we would have talked about clothes, about summer things like towels as we dried, salty, back on the beach.

Written for Emma Fitts’ exhibition Mountain Shadows and Water Colours at The National, Ōtautahi, 2020.

[1] Crustose lichens form a crust,

usually on rocks or trees, often becoming inseparable from the substrate. There

are also ‘foliose’ lichens which grow in rosette-like layers, and ‘fruticose’,

which are spiny, wiry. Maggy

Wassilieff, ‘Lichens in New Zealand,’ Te

Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, 24 September 2007: https://teara.govt.nz/en/lichens/page-2.

[2] Ngā Kōhatu Whakarekareka o Tamatea Pōkai Whenua are the smouldering boulders of Tamatea Pōkai Whenua. Listen to Donald Couch’s (Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu) recorded narrative here: https://my.christchurchcitylibraries.com/ti-kouka-whenua/rapaki-marae/.

[3] Crustose lichens form a biological layer of the surface they adhere to, sometimes sitting within the tissue itself.

[4] Wassilieff, 2007.

[5] See ‘Lichens of New Zealand Checklist’: https://inaturalist.nz/lists/336390-Lichens-of-NZs-Check-List.

[2] Ngā Kōhatu Whakarekareka o Tamatea Pōkai Whenua are the smouldering boulders of Tamatea Pōkai Whenua. Listen to Donald Couch’s (Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu) recorded narrative here: https://my.christchurchcitylibraries.com/ti-kouka-whenua/rapaki-marae/.

[3] Crustose lichens form a biological layer of the surface they adhere to, sometimes sitting within the tissue itself.

[4] Wassilieff, 2007.

[5] See ‘Lichens of New Zealand Checklist’: https://inaturalist.nz/lists/336390-Lichens-of-NZs-Check-List.

[6] Derek Grzelewski, ‘The Microscopic World of Lichens,’ New Zealand Geographic 109, May-June

2011 https://www.nzgeo.com/stories/the-microscopic-world-of-lichens/.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Paul Simons, ‘Lichens: hardy organisms warm of pollution and climate change,’ The Guardian, 18 December 2018:https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/dec/18/lichens-hardy-organisms-warn-of-pollution-and-climate-change.

[9] Jean-Pierre de Vera, ‘Lichens as survivors in space and on Mars,’ Fungal Ecology 5:4 (2012), 472-479: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1754504812000098.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Paul Simons, ‘Lichens: hardy organisms warm of pollution and climate change,’ The Guardian, 18 December 2018:https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/dec/18/lichens-hardy-organisms-warn-of-pollution-and-climate-change.

[9] Jean-Pierre de Vera, ‘Lichens as survivors in space and on Mars,’ Fungal Ecology 5:4 (2012), 472-479: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1754504812000098.