Lichen is a contract

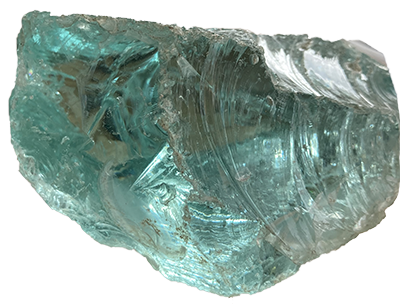

Lichen is a contract. That is, it exists as

the result of a relationship between organisms from two, sometimes three

different ‘kingdoms.’[1] I

picture it like this. Kingdom Fungi: slow moving and damp, breathing whiffs of

mushroom, compost, and yeast from its planty tissue. Kingdom Algae: a loose

textile of restless, glinting filaments of light, the air itself turning

slightly green as it comes into contact. Sometimes there is bacteria too,

Kingdom Monera: single-celled organisms that have no membrane, are almost just a

pore, a process. The fungi structure protects the more vulnerable algae—the

fungi is what you see when you identify lichen. The algae cells, nested within,

do the work of photosynthesis, producing carbohydrates to sustain the whole.[2]

I spoke to Emma about her new works in August, and wrote about them,[3] mainly about the loose canvases photographed along the Port Hills crater rim, Ngā Kōhatu Whakarekareka o Tamatea Pōkai Whenua.[4] These works were something like lichen I thought. Lichens are what the bone-hard rock shoulders up there wear—or, they wear each other, the microorganism and the terrain, who is to say?[5] The lichen may be wearing the rocks, the rocks wearing the light, which is in turn held close by the photosynthetic lichen. The lichen metaphor still rests well in my mind: the co-reliant organism, and the new works—these too could be thought of as a kind of contract. In the making process, the flashe and acrylic solution saturates the canvas, holding and bending the light, like algae, so that it emerges acidic and luminous in some works, muted in others. The canvas holds the weight of that process, drying pigment-loaded, a layered or folded structure, starchy as lichen. For weeks now I have seen lichen everywhere, like there is a filter on my eyes.

There is a point when a metaphor changes though, becomes something that you wake up with and can feel on your skin, becomes a garment itself. This is not the first time these works have been thought about as something to be worn. A series of works (initially developed from research while Emma was resident at McCahon House, Titirangi, in 2017) reference a backstrap loom, which is worn on the body while the weaver works. ‘Worn’ is only an approximate word for this relationship—leaning into the loom backstrap, the weaver’s backbone and chest, at least, are the loom, along with two wooden poles between which the warp is stretched. In the Christchurch Art Gallery Touching Sight installation, hung from wooden poles, these works still remember the movements of the working body, the twist of a torso and resistance of bone. The slack fall of cotton rope seems ready to be stepped into, become taut again with the working of the maker’s back and arms.

Then there are a series of ‘envelope’ works, referencing the garments of French designer Madeleine Vionnet (1876-1975). Vionnet’s dresses were cut on the bias—following the shape of the body and making redundant undergarments like corsets. Bias cut dresses were easy to get in and out of and to move in, loose envelopes for the body’s structure, which in turn lent them support, volume, blood-warmth. These works seem to rest against the wall, answering only to the diagonal seams and the points at which they are fixed for their form. It’s not that they ‘clothe’ the wall. Rather, the walls and the works lean on each other. Look closely; the air around them almost shivers with that equilibrium.

I’ve never actually been in the same room with this work though, seen it on the walls. Lock-down and the distance between Tāmaki Makaurau and Ōtautahi mean that I have seen it in emailed jpegs only. Maybe this is why the metaphors have been so real to me, as if seeing alone is not, this time, enough. I open up the images of Emma’s work on my laptop again, zoom in until I find the grain of the canvas and its chalky pigment, in contrast to the gleam of the screen. There is another contract at play. If I angle the light on the screen just right, at the correct diagonal, it’s like the canvases are wet again, soaked in the light from the window by my desk.

I spoke to Emma about her new works in August, and wrote about them,[3] mainly about the loose canvases photographed along the Port Hills crater rim, Ngā Kōhatu Whakarekareka o Tamatea Pōkai Whenua.[4] These works were something like lichen I thought. Lichens are what the bone-hard rock shoulders up there wear—or, they wear each other, the microorganism and the terrain, who is to say?[5] The lichen may be wearing the rocks, the rocks wearing the light, which is in turn held close by the photosynthetic lichen. The lichen metaphor still rests well in my mind: the co-reliant organism, and the new works—these too could be thought of as a kind of contract. In the making process, the flashe and acrylic solution saturates the canvas, holding and bending the light, like algae, so that it emerges acidic and luminous in some works, muted in others. The canvas holds the weight of that process, drying pigment-loaded, a layered or folded structure, starchy as lichen. For weeks now I have seen lichen everywhere, like there is a filter on my eyes.

There is a point when a metaphor changes though, becomes something that you wake up with and can feel on your skin, becomes a garment itself. This is not the first time these works have been thought about as something to be worn. A series of works (initially developed from research while Emma was resident at McCahon House, Titirangi, in 2017) reference a backstrap loom, which is worn on the body while the weaver works. ‘Worn’ is only an approximate word for this relationship—leaning into the loom backstrap, the weaver’s backbone and chest, at least, are the loom, along with two wooden poles between which the warp is stretched. In the Christchurch Art Gallery Touching Sight installation, hung from wooden poles, these works still remember the movements of the working body, the twist of a torso and resistance of bone. The slack fall of cotton rope seems ready to be stepped into, become taut again with the working of the maker’s back and arms.

Then there are a series of ‘envelope’ works, referencing the garments of French designer Madeleine Vionnet (1876-1975). Vionnet’s dresses were cut on the bias—following the shape of the body and making redundant undergarments like corsets. Bias cut dresses were easy to get in and out of and to move in, loose envelopes for the body’s structure, which in turn lent them support, volume, blood-warmth. These works seem to rest against the wall, answering only to the diagonal seams and the points at which they are fixed for their form. It’s not that they ‘clothe’ the wall. Rather, the walls and the works lean on each other. Look closely; the air around them almost shivers with that equilibrium.

I’ve never actually been in the same room with this work though, seen it on the walls. Lock-down and the distance between Tāmaki Makaurau and Ōtautahi mean that I have seen it in emailed jpegs only. Maybe this is why the metaphors have been so real to me, as if seeing alone is not, this time, enough. I open up the images of Emma’s work on my laptop again, zoom in until I find the grain of the canvas and its chalky pigment, in contrast to the gleam of the screen. There is another contract at play. If I angle the light on the screen just right, at the correct diagonal, it’s like the canvases are wet again, soaked in the light from the window by my desk.

Written for Emma Fitts, Touching Sight (with Conor Clarke and Oliver Perkins), curated by Melanie Oliver, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Ōtautahi, 2020. Originally published in B.202.

[1] More on this can be found

at Derek Grzelewski, ‘The Microscopic World of Lichens,’ New Zealand Geographic 109, May-June 2011.

[2] This is of course not the extent of the series of exchanges that form lichen; think of the rain, the metallic or porous surfaces on which lichen grows. Once you start thinking about and googling any one part of an ecological whole you recognise, again, that it is an interconnected system far more complex than the internet itself. See Maggy Wassilieff, ‘Lichens in New Zealand,’ Te Ara, the Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, 24 September 2007.

[2] This is of course not the extent of the series of exchanges that form lichen; think of the rain, the metallic or porous surfaces on which lichen grows. Once you start thinking about and googling any one part of an ecological whole you recognise, again, that it is an interconnected system far more complex than the internet itself. See Maggy Wassilieff, ‘Lichens in New Zealand,’ Te Ara, the Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, 24 September 2007.

[3] ‘Lichen like light’, Emma

Fitts: Mountain shadows and watercolours, 18 August – 5 September 2020, The

National, Ōtautahi Christchurch.

[4] Ngā Kōhatu Whakarekareka o Tamatea Pōkai Whenua are the smouldering boulders of Tamatea Pōkai Whenua. Listen to Donald Couch’s (Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu) recorded narrative here.

[5] Some lichens form a biological layer of the surface they adhere to, sitting within the substrate itself.

[4] Ngā Kōhatu Whakarekareka o Tamatea Pōkai Whenua are the smouldering boulders of Tamatea Pōkai Whenua. Listen to Donald Couch’s (Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu) recorded narrative here.

[5] Some lichens form a biological layer of the surface they adhere to, sitting within the substrate itself.