A voice suggests (expects, demands) a body

There are three works by Alicia

Frankovich in the exihibition Can Tame Anything.

There is a video called Exoplanets: Probiotics Probiotics!,

two large suspended photographic prints on PVC called After Blue Marble: Mouth Bacteria I and II, and a vinyl wall work called Microchimerism. At a simple level, each might be considered a

performance in the realm of microbiology. These perfomances occur, respectively,

in a home-cultured probiotic drink, a site exterior to the human body; in the

mouth or entranceway to the body; and within the deep interiority of the biological

body, in the DNA structure itself.[1] Each is approached as a scene of lively encounter, of minute and significant differentiation:

between what exists outside and inside the body, between ‘self’ and other forms

of organic life.

I enjoy finding this descending pattern of three. I begin here. I think: through these sites of biological activity we might think about the displacement of the individual self, into infinitely microscopic cells, a diffusion of selfhood, so that it is registered on a biological scale rather than within a giant and self-contained ‘I’. Thinking about the clean diagram of this reading, and the scale shift it entails, I feel the small and habitually tensed muscles in my jaw and round my eyes relax. Paradoxically, the ‘I’ which I recognise as myself is consistently eased by the idea that this same self is also a cultural construction, something which could be re-conceptualised as more porous, more soluble, less finished.

As materialist feminists have long been aware, acknowledging matter at a microbial scale is a political act: the conventional binary differention of scale is itself a gendered power relationship. Physicist and philosopher Karen Barad points out that the belief that the world is separated into macro and micro, with classical physics applied to the macro and quantum physics to the micro, “suggests that at a particular scale, one conveniently accessible to the human, a rupture exists in the physics and ontology of the world.”[2] In this scheme ‘normal’ things are macro, while the micro is restricted to a kind of sub-humanity, and “any danger of infection or contamination of any kind is removed in this strict quarantining of all queer Others.”[3]

Breaking with this binary means interpolating the solidity of the humanist ‘I’ with a series of organic processes, such as those of digestion and immunity, eating, sleeping, aging, disease, cell formation and development. It means recognising that matter holds forms of agency,[4] and that being itself is essentially relational. Rather than as discrete entities, humans may be seen to function both as and within a material ecology.[5]

Frankovich’s recent work is frequently framed as posthumanist in its elastic reach for the plural possibilities and performances of selfhood. As her practice has always suggested though, it’s important to hold conceptual conversations about selfhood close to the recognition of physical bodies in the encounter with this work. How then are multiple physical bodies present at each of the sites in this work? How do they perform in relationship to what we conventionally call ‘our’ selves? How do they speak in this work, how do we hear them, and in hearing, what do we hear? Or flip it back the other way, as Quinn Latimer does in a recent text on the reader-writer relationship: “[But] a voice suggests (expects, demands), a body.”[6]

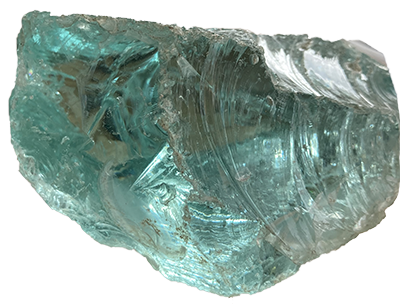

I didn’t see this exhibition; I am far away. Too far away really, now sitting writing at a desk in the summer after the exhibition, far from from the living bodies which provide the information for these works. I download and watch the video Exoplanets: Probiotics Probiotics!, following the unfolding fluorescence of blue crystals on the screen. I have been making kimchi in the morning, another probiotic fermentation; the smell is still on my hands, mildly sulphurous but not unpleasant. After I watch the video I leave the room and my laptop and go to check on it. It’s hot in the concrete apartment and already the cabbage and carrot and onion are bubbling gently inside the jars. They glow, luridly alive, in their own juice.

I enjoy finding this descending pattern of three. I begin here. I think: through these sites of biological activity we might think about the displacement of the individual self, into infinitely microscopic cells, a diffusion of selfhood, so that it is registered on a biological scale rather than within a giant and self-contained ‘I’. Thinking about the clean diagram of this reading, and the scale shift it entails, I feel the small and habitually tensed muscles in my jaw and round my eyes relax. Paradoxically, the ‘I’ which I recognise as myself is consistently eased by the idea that this same self is also a cultural construction, something which could be re-conceptualised as more porous, more soluble, less finished.

As materialist feminists have long been aware, acknowledging matter at a microbial scale is a political act: the conventional binary differention of scale is itself a gendered power relationship. Physicist and philosopher Karen Barad points out that the belief that the world is separated into macro and micro, with classical physics applied to the macro and quantum physics to the micro, “suggests that at a particular scale, one conveniently accessible to the human, a rupture exists in the physics and ontology of the world.”[2] In this scheme ‘normal’ things are macro, while the micro is restricted to a kind of sub-humanity, and “any danger of infection or contamination of any kind is removed in this strict quarantining of all queer Others.”[3]

Breaking with this binary means interpolating the solidity of the humanist ‘I’ with a series of organic processes, such as those of digestion and immunity, eating, sleeping, aging, disease, cell formation and development. It means recognising that matter holds forms of agency,[4] and that being itself is essentially relational. Rather than as discrete entities, humans may be seen to function both as and within a material ecology.[5]

Frankovich’s recent work is frequently framed as posthumanist in its elastic reach for the plural possibilities and performances of selfhood. As her practice has always suggested though, it’s important to hold conceptual conversations about selfhood close to the recognition of physical bodies in the encounter with this work. How then are multiple physical bodies present at each of the sites in this work? How do they perform in relationship to what we conventionally call ‘our’ selves? How do they speak in this work, how do we hear them, and in hearing, what do we hear? Or flip it back the other way, as Quinn Latimer does in a recent text on the reader-writer relationship: “[But] a voice suggests (expects, demands), a body.”[6]

I didn’t see this exhibition; I am far away. Too far away really, now sitting writing at a desk in the summer after the exhibition, far from from the living bodies which provide the information for these works. I download and watch the video Exoplanets: Probiotics Probiotics!, following the unfolding fluorescence of blue crystals on the screen. I have been making kimchi in the morning, another probiotic fermentation; the smell is still on my hands, mildly sulphurous but not unpleasant. After I watch the video I leave the room and my laptop and go to check on it. It’s hot in the concrete apartment and already the cabbage and carrot and onion are bubbling gently inside the jars. They glow, luridly alive, in their own juice.

1

Because I am here, in the kitchen, walking back to the desk, let’s start with thinking about the bodies in Exoplanets: Probiotics Probiotics! The video is made up of thousands of stills of the microbiota in water kefir, photographed at the Centre for Advanced Microscopy (Australian National University). These appear as luminous, swimming on a dark ground. The image is accompanied by a voice track, reading fragments of text. At some points this sounds like a simple recipe for the drink water kefir; at others it is more existential: “things that I take, I swallow.” At some fluid threshold of the self, somewhere between swallow and stomach, these bacterial bodies become part of our own.

Probiotic bacteria, such as those found in water kefir, occur through fermentation, producing enzymes, acids and proteins that are said to improve gut health. While longstanding hygiene-oriented rhetoric suggests humans are at ‘war’ with bacteria, requiring us to fortify our bodies against germs, there is a growing counter-movement through the probiotics industry, within which wellbeing begins with the presence of ‘good bacteria’ in the digestive system.

In a contemporary capitalist context, where consumption and selfhood may often be seen as correlative—consumption as an expression of who we are; the bodies we consume in the performance of self-transformation—water kefir presents a distinct exception. Frankovich points out that kefir is a ‘free’ phenomenon, the crystals typically gifted from an existing bug, and that it is able to be sustained with just water, sugar and lemon and some dried fruit every three days. Water kefir is not usually able to be purchased in shops, rather circulates in a gifting economy. As such it relies on a community network as well as ongoing acts of nourishment to keep the bacteria alive.

The human microbiome, or community of bacteria, fungi and viruses hosted by our bodies, is receiving increasing attention in biological and medical research. Science journalist Richard Conniff writes, “We tend to think that we are exclusively a product of our own cells, upwards of ten trillion of them. But the microbes we harbor add another 100 trillion cells into the mix.”[7] The maths are necessarily reductive but they make a significant point: if we count cells as the matter which makes us human, this forms only one-tenth of our bodies as functioning organisms. This opens to an understanding of the self as a form of host, or an activity of hosting; the idea that to be alive is, irreduceably, a symbiotic companionship with other material bodies.

There is the reference to something else within Exoplanets: Probiotics Probiotics! though: an exoplanet, or planet outside of our solar system. Exoplanets belong to other solar systems, orbit their own star-like suns; by statistical probability, some may occupy the ‘habitable zone’.[8] Our closest exoplanet is Proxima Centauri B, 4.2 light years away from Earth. The exoplanet evokes a vastly distant exteriority—and yet, within the scope of this work there’s a relatable resonance. As the voice-over says: “I grow you / inside, outside / these are the planets that we do not know / this is the inside of me.” Probiotic bacteria and exoplanets may be said to represent the farthest conceivable poles of human ‘inhabitance’. As such there is between them a difference in degree, not kind. Extra-solar space and the microbial universe that is “growing, orbiting, with us”: both projections of ourselves that are at once intimate and distant.

2

In the second work, After Blue Marble: Mouth Bacteria I and II, there is the mouth, its bacteria imaged in using microscopic photographic technology. ‘Blue marble’ is the name of the image of Earth taken from space on 7 December 1972 by astronauts on the Apollo. That image was almost ten years old when I was born; I grew up with a poster of the image in the bathroom door, and have just realised it’s still here on the wall in my flat, a faded banner of a photograph so ubiquitous I barely register it. What comes ‘after’ such hyper-reproduction?

After Blue Marble: Mouth Bacteria I and II (originally commissioned as a series of public billboards for Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria, 2018) might be read as Frankovich’s response to the contemporary impossibility, or philosophical imprecision, of a singular anthropocentric perspective. In these two photographs the lens is turned internally, to a site where life proliferates, largely unseen and beyond any identifiable sense of the self as an individual. Frankovich writes: “These interior spaces become inversions: surfaces of forms exploring the resonances between micro-processes and macro-ecologies. Artificial hormones and antibiotics become fluid continents; the microscope becomes a telescope.”[9] Rather than looking back telescopically from the distance of space, this view is of the unknown terrain that we embody as material organisms. The blue marble image is turned in on itself; the ‘I’ is turned inside out.

The mouth is where the voice resides, where we speak from; it is where we take in nourishment and remedies, oxygen, and from which we expel carbon dioxide. It is also where swabs are taken for testing. There are over 1,000 possible microbial species in our mouths,[10] making it a key site from which samples are taken and grown in a petri dish, and DNA sequences read from. As well as taking in what the external world offers, what the air carries, what is to be swallowed down, breathed in, spat out, the mouth is a body of information in itself. As such it’s a site of multiple expressions, performances of self-identity, and a place of meeting with other bodies.

3

This takes us deeper into the interiority of the body, to the third work, Microchimerism.In Microchimerism Frankovich’s DNA profile (karotype) is recorded. The original data was taken from a blood sample, and mapped according to a standard female chromosome profile. This information was then magnified and reproduced as a series of forms in gold vinyl, applied like skin to the wall. Pink variants of the forms are more scant and interspersed throughout the gold. These suggest foreign DNA that may be inside Alicia’s body.

I saw this work (in a later iteration) at Starkwhite in Auckland.[11] Sharing a physical space with both work, I was taken back to the scale inversion that had started my thinking about this work. In the exhibition the DNA returns to a form of embodiment. Dislocated from the analytical logic of the recorded sequence, it is re-materialised here in relation to the room and its contours, a composite of private biological script and the public architectural space it temporarily inhabits. Necessarily abstracted, and on a large scale, I finally experienced these microscopically-imaged bodies as taking up space, as public forms. It was here, seeing them on the wall where they appear almost to swim in one’s vision, that I started to think of how DNA moves fluidly between biological or scientific discourse and social meaning.

A microchimera is a single organism that is host to DNA cells from another organism or organisms. For example, a mother’s body may retain cells from her child through pregnancy. Equally, siblings may inherit cells from each other, in utero, rather than through a parent. Microchimerism can also occur through blood transfusion or organ transplant. While heredity tends to be associated with traits passed ‘down’ through generations, contemporary genetic research continues to reveal the multiple ‘horizontal’ and non-linear relationships that genetic organisms participate in, and in so doing, to complicate the concept of how genetic material is shared, to include the microbiome, epigenetics,[12] and cultural experience. In this sense microchimerism embodies a contradiction, and a question that has also been a central concern of Frankovich’s recent work: the primacy of a whole or true ‘self’ that underpins it is at some level destablised by that same science.

Meehan Crist, current writer in residence in biological sciences at Columbia, notes that horizontal inheritance makes up to eight percent of the human genome; some of our DNA actually comes from viruses that enter human cells at the reproductive phase, and are then passed on. She points out that not only do such viruses make pregnancy possible, their presence means that humans are at birth the fusion of different species’ DNA.[13] As Crist argues, “certain relationships are culturally valued [over others]”, pointing out that since ancient Roman law the recording of heredity (linguistically related to ‘heir’) can be linked to an agenda of power and the consolidation of assets—ensuring that wealth was passed down through families.

In the case of linear inheritance, it’s an idea that has also scaffolded the hetero-patriarchal project of colonisation, justified by the biological inheritance of race, inherited ‘superiority’:

Specious biological categories have long been used to bolster racist or xenophobic speculation about inherent differences between people and cultures, but modern genetics makes notions of racial ‘purity’ laughable, and shows them to be rooted in cultural and political desires that have nothing to do with biology.[14]

To reframe genetic inheritance as multiple—the line of thought prompted throughout this work—is then not only to begin to undermine the biological singularity of the human individual, but with it an oppressive politics of individualism.

Reader, writer, listener

But I fear getting lost in all this. How to reconcile the physicality of the known body, the me that sits here at the laptop, reading, or making kimchi, with a more diffuse sense of self, dispersed through myriad microscopic bodies and across three sites of attention in this work? Where is the hinge, where is the relationship that keeps me—as writer, reader, viewer of the work—from floating into the dematerialised abstraction of scientific account?

Perhaps the work offers one further, and intersecting, way to think through dispersed selfhood: through the co-constitutive gestures of writing, reading, and listening that it initiates. Quinn Latimer’s essay ‘Signs, Sounds, Metals, Fires’ considers the structural relationships embodied in archaic and classical Greek language, that of writer (a patriarchal figure), text (a daughter figure) and reader (a suitor figure), who would give the text voice, making it audible.[15]

In her text Latimer devolves the hierarchy of this structure, making space for a different configuration of relationships which include the reader, and the listener or ‘receiver’. Importantly, this inter-relationship is described on physical terms—those of the body, those of gesture. Latimer writes, “The listener takes the reader’s voice into her; the reader will take the writer’s voice into her. She is the writer’s vessel, her instrument. The reader beckons the receiver; someone must recognise her sounds. The writer beckons the reader; someone must read her signs.”[16]

The Exoplanets: Probiotics Probiotics! text is written by Frankovich, read by Nadia Bekkers. Bekkers reads a form of poem (“a biological interior…becomes a planet…I grow you”), including scientific optical instruments (dark field illuminator) as well as a recipe for fermentation (a slice of fig, 40 degrees, water, sugar, lemon). When I hear this I recognise some of its signs. I hear a woman speaking about health. I hear the politics of resistance toward an entrenched differentiation of scale that dislocates us from the microscopic, and in so doing dislocates us from our own bodies, dislocates us from the vastness of the universe. I hear a voice, the embodiment of written text, and within this experience, a multitude of other voices are present.

Language—spoken, written, received—is part of what enables this recognition. I listen, and as I listen I take in. To return to Latimer’s assertion, “a voice suggests (expects, demands) a body.”[17] Frankovich’s installation is a space in which the voices of numerous microbiological forms of life are foregrounded. It’s not necessarily that I ‘hear’ these voices in the work, but rather, as a viewer, listener, and later as a writer, I am momentarily but acutely aware of their embodiment, and of my own physicality, which is the physicality of infinite organic relationships. It is like…it is like being…no, not like—but actually, this is a body.

This relational, but also physically connecting capacity of the voice in the work might also be extended the text—this text, that I am writing, that are you reading. I again borrow this thought from Latimer: “The writer writes for the future (reader)....The act of writing and reading itself is an apprehension of the present, a holding of it in one’s hand or mouth.”[18] The exhibition is finished but here in the present, between us, there this voice, this body of text that may be held. And you: you are here.

But I fear getting lost in all this. How to reconcile the physicality of the known body, the me that sits here at the laptop, reading, or making kimchi, with a more diffuse sense of self, dispersed through myriad microscopic bodies and across three sites of attention in this work? Where is the hinge, where is the relationship that keeps me—as writer, reader, viewer of the work—from floating into the dematerialised abstraction of scientific account?

Perhaps the work offers one further, and intersecting, way to think through dispersed selfhood: through the co-constitutive gestures of writing, reading, and listening that it initiates. Quinn Latimer’s essay ‘Signs, Sounds, Metals, Fires’ considers the structural relationships embodied in archaic and classical Greek language, that of writer (a patriarchal figure), text (a daughter figure) and reader (a suitor figure), who would give the text voice, making it audible.[15]

In her text Latimer devolves the hierarchy of this structure, making space for a different configuration of relationships which include the reader, and the listener or ‘receiver’. Importantly, this inter-relationship is described on physical terms—those of the body, those of gesture. Latimer writes, “The listener takes the reader’s voice into her; the reader will take the writer’s voice into her. She is the writer’s vessel, her instrument. The reader beckons the receiver; someone must recognise her sounds. The writer beckons the reader; someone must read her signs.”[16]

The Exoplanets: Probiotics Probiotics! text is written by Frankovich, read by Nadia Bekkers. Bekkers reads a form of poem (“a biological interior…becomes a planet…I grow you”), including scientific optical instruments (dark field illuminator) as well as a recipe for fermentation (a slice of fig, 40 degrees, water, sugar, lemon). When I hear this I recognise some of its signs. I hear a woman speaking about health. I hear the politics of resistance toward an entrenched differentiation of scale that dislocates us from the microscopic, and in so doing dislocates us from our own bodies, dislocates us from the vastness of the universe. I hear a voice, the embodiment of written text, and within this experience, a multitude of other voices are present.

Language—spoken, written, received—is part of what enables this recognition. I listen, and as I listen I take in. To return to Latimer’s assertion, “a voice suggests (expects, demands) a body.”[17] Frankovich’s installation is a space in which the voices of numerous microbiological forms of life are foregrounded. It’s not necessarily that I ‘hear’ these voices in the work, but rather, as a viewer, listener, and later as a writer, I am momentarily but acutely aware of their embodiment, and of my own physicality, which is the physicality of infinite organic relationships. It is like…it is like being…no, not like—but actually, this is a body.

This relational, but also physically connecting capacity of the voice in the work might also be extended the text—this text, that I am writing, that are you reading. I again borrow this thought from Latimer: “The writer writes for the future (reader)....The act of writing and reading itself is an apprehension of the present, a holding of it in one’s hand or mouth.”[18] The exhibition is finished but here in the present, between us, there this voice, this body of text that may be held. And you: you are here.

This essay was originally published in Embodied Knowledge/Can Tame Anything, edited by Melanie Oliver, for the exhibitions Embodied Knowledge and Can Tame Anything at The Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt, 2018.

[1] In a recent project, for which the film Exoplanets:

Probiotics Probiotics! was commissioned,

the exhibition itself was conceived as a series of cavities, the body and

architecural forms as hosting microscopic and macroscopic worlds. See Hannah

Mathews, exhibition text, Alicia

Frankovich; Exoplanets, Monash University Museum of Art (Melbourne), 6

October – 15 December 2018.

[2] In this interview Barad addresses a common misconception that her theory of ‘agential realism’ means applying quantum physics as a form of analogy for the social world of people. Rather, Barad’s aim is to look at the metaphysical assumptions that underpin—and conventionally separate—the two. In questioning this dualism her assertion is not that scale doesn’t matter, but that the way scale is produced should be part of the discussion. See Malou Juelskjær and Nete Schwennesen, ‘Intra-active Entanglements, an Interview with Karen Barad,’ Kvinder, Kon and Forskning 1-2 (2012): 17-18.

[3] Ibid, 18.

[4] For a full discussion of Barad’s agential realism, see ‘Matter Feels, Converses, Suffers, Desires, Yearns and Remembers: Interview with Karen Barad,’ New Materialism: Interviews and Cartographies, edited by Rick Dolphijn and Iris Van der Tuin, np. (Michigan: Open Humanities Press, 2012).

[5] This is not new knowledge. Most relevant in this place, Aotearoa, is the Te Ao Māori principal of whakapapa, which situates humans in relation to the Earth, Papatūānuku. Emilie Rākete (Ngāpuhi) writes of this relationship: “From a political ecological perspective rooted in Papatūānuku, we could translate ‘tangata whenua’ . . . as ‘land-people’—‘people’ not as its own epistemological category, but as a function of the land, of the whenua. We are not beings who are of the land but the land itself in the act of being. We are a function of the ecology, we are ecology foremost.” Ecology is a biological designation; the model here is that of organisms within a system, their relationship to each other, and their surroundings. Rākete, “In Human: Posthumanism, Parasites, Papatūānuku,” Anarchic Cannibalism, accessed 15 January 2015: http://anarchacannibalism.tumblr.com/post/99890543754/in-human-parasites-posthumanism-papat%C5%AB%C4%81nuku.

[6] Quinn Latimer, ‘Signs, Sounds, Metals, Fires, or An Economy of Her Reader’, Like a Woman(Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2017), 205.

[7] Richard Conniff, ‘Microbial Research: The Trillions of Creatures Governing Your Health’, Smithsonian Magazine, May 2013. www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/microbes-the-trillions-of-creatures-governing-your-health

[2] In this interview Barad addresses a common misconception that her theory of ‘agential realism’ means applying quantum physics as a form of analogy for the social world of people. Rather, Barad’s aim is to look at the metaphysical assumptions that underpin—and conventionally separate—the two. In questioning this dualism her assertion is not that scale doesn’t matter, but that the way scale is produced should be part of the discussion. See Malou Juelskjær and Nete Schwennesen, ‘Intra-active Entanglements, an Interview with Karen Barad,’ Kvinder, Kon and Forskning 1-2 (2012): 17-18.

[3] Ibid, 18.

[4] For a full discussion of Barad’s agential realism, see ‘Matter Feels, Converses, Suffers, Desires, Yearns and Remembers: Interview with Karen Barad,’ New Materialism: Interviews and Cartographies, edited by Rick Dolphijn and Iris Van der Tuin, np. (Michigan: Open Humanities Press, 2012).

[5] This is not new knowledge. Most relevant in this place, Aotearoa, is the Te Ao Māori principal of whakapapa, which situates humans in relation to the Earth, Papatūānuku. Emilie Rākete (Ngāpuhi) writes of this relationship: “From a political ecological perspective rooted in Papatūānuku, we could translate ‘tangata whenua’ . . . as ‘land-people’—‘people’ not as its own epistemological category, but as a function of the land, of the whenua. We are not beings who are of the land but the land itself in the act of being. We are a function of the ecology, we are ecology foremost.” Ecology is a biological designation; the model here is that of organisms within a system, their relationship to each other, and their surroundings. Rākete, “In Human: Posthumanism, Parasites, Papatūānuku,” Anarchic Cannibalism, accessed 15 January 2015: http://anarchacannibalism.tumblr.com/post/99890543754/in-human-parasites-posthumanism-papat%C5%AB%C4%81nuku.

[6] Quinn Latimer, ‘Signs, Sounds, Metals, Fires, or An Economy of Her Reader’, Like a Woman(Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2017), 205.

[7] Richard Conniff, ‘Microbial Research: The Trillions of Creatures Governing Your Health’, Smithsonian Magazine, May 2013. www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/microbes-the-trillions-of-creatures-governing-your-health

[8] The habitable zone relates to the possible presence of

liquid water (in the right climate conditions) on Earth-like planets orbiting

their own stars.

[9] Artist note.

[10] “It’s not just that there are more than 1,000 possible microbial species in your mouth. The census, as it currently stands, also counts 150 behind your ear, 440 on the insides of your forearm and any of several thousand in your intestines. In fact, microbes inhabit almost every corner of the body, from belly button to birth canal, all told more than 10,000 species. Looked at in terms of the microbes they host, your mouth and your gut are more different than a hot spring and an ice cap.” Conniff, ibid.

[11] Alicia Frankovich, Starkwhite, Auckland, 6 February - 8 March2019. Here it was shown alongside the water kefir video.

[12] Epigenetics is the study of things that affect how cells read or express DNA; that is, biological factors which operate in addition to genetic material. These might include age, lifestyle and diseases.

[13] “So whenever humans have a child, we’re passing down, via vertical heredity, viral genes inserted sideways into our genomes via horizontal heredity. In fact, we wouldn’t be able to reproduce at all without horizontal heredity. A crucial membrane between foetus and placenta exists thanks to a viral gene from one of those retroviral horizontal transfers. That viral gene makes all mammalian pregnancy possible. So at the level of DNA, humans are actually a mash-up of different species.” Meehan Crist, ‘Race Doesn’t Come Into It’ [a review of Carl Zimmer’s She Has Her Mother’s Laugh: The Powers, Peversions and Potentials of Heredity, 2018], London Review of Books, vol. 40, no. 20, 25 October 2018, 9.

[14] Ibid., 10.

[15] The orientation here was oral language: “What was remarkable in ancient Greece was what sounded. What achieved an audible reknown. What was read—out loud.” Latimer, ‘Signs, Sounds, Metals, Fires...’, 204.

[16] Ibid., 205.

[17] Ibid., 206.

[18] Ibid., 219-20.

[9] Artist note.

[10] “It’s not just that there are more than 1,000 possible microbial species in your mouth. The census, as it currently stands, also counts 150 behind your ear, 440 on the insides of your forearm and any of several thousand in your intestines. In fact, microbes inhabit almost every corner of the body, from belly button to birth canal, all told more than 10,000 species. Looked at in terms of the microbes they host, your mouth and your gut are more different than a hot spring and an ice cap.” Conniff, ibid.

[11] Alicia Frankovich, Starkwhite, Auckland, 6 February - 8 March2019. Here it was shown alongside the water kefir video.

[12] Epigenetics is the study of things that affect how cells read or express DNA; that is, biological factors which operate in addition to genetic material. These might include age, lifestyle and diseases.

[13] “So whenever humans have a child, we’re passing down, via vertical heredity, viral genes inserted sideways into our genomes via horizontal heredity. In fact, we wouldn’t be able to reproduce at all without horizontal heredity. A crucial membrane between foetus and placenta exists thanks to a viral gene from one of those retroviral horizontal transfers. That viral gene makes all mammalian pregnancy possible. So at the level of DNA, humans are actually a mash-up of different species.” Meehan Crist, ‘Race Doesn’t Come Into It’ [a review of Carl Zimmer’s She Has Her Mother’s Laugh: The Powers, Peversions and Potentials of Heredity, 2018], London Review of Books, vol. 40, no. 20, 25 October 2018, 9.

[14] Ibid., 10.

[15] The orientation here was oral language: “What was remarkable in ancient Greece was what sounded. What achieved an audible reknown. What was read—out loud.” Latimer, ‘Signs, Sounds, Metals, Fires...’, 204.

[16] Ibid., 205.

[17] Ibid., 206.

[18] Ibid., 219-20.