A greengage sea

Last night at

dinner, we were talking about huskies and dogsleds in Alaska. Deborah’s dad has

been on one, and he said how quiet it was, except for the dogs’ breathing, and

the skiffing sound of the sled’s steel runners along the snow. The conversation

moved to ice melting, to Iceland, to someone’s agate wrist bracelet smashing

into smithereens on the pavement when she fell. It moved off again, to recent floods

and Auckland’s drought, to the drainage of Waikato swamps for farming and the raging

peat fires that sometimes ensued. Deborah’s dad said peat tastes like smoke, or

maybe it’s the other way round. I still had the skiffing sound in my ears, the

incandescent burn of ice cold in my eyes.

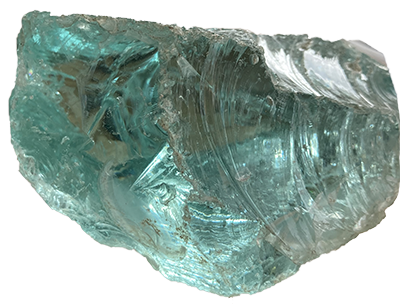

The ‘greengage sea’ comes from Ice by Anna Kavan, a book and a writer Georgie introduced me to. It’s the kind of image that almost gets lost in the turbulence of Kavan’s writing. In Ice the narrative hinges on an ice age, possibly due to nuclear detonation, and an unspecified geopolitical crisis. The often-terrifying descriptions of the climate glitter, and sometimes shatter, under their own intensity. Sometimes, they seem to relate in an oblique way to Georgie’s work, to feed from a similar light source. I read, “…sheathed in ice, [the trees] dripped and sparkled with weird prismatic jewels, reflecting the vivid changing cascades above.” You do you see it, don’t you—ice fracturing the light, the light exploding like an iris, or turning in on itself like a shell? It may be that it’s Georgie’s most recent paintings that are reflected in the iced trees, images within Kavan’s image.

Of Ice, a critic notes: “…the reader cannot distinguish between material reality and the hectic projection of the hero, who admits: “I had a curious feeling I was living on several planes simultaneously; the overlapping of these planes was confusing.”[1]I don’t really agree; the ‘hectic projection’ of the unnamed, misogynistic hero is I think clearly distinct from the material reality of the story. As a reader, disassociated from the protagonist and his predatory, narrative-driving instinct, it is the catastrophic magnificence of the environment that I experience most vividly. In this sense the book feels almost empty of human presence, certainly, of empathy. Instead of actors, there is an architecture of planes, surfaces reflecting the impossible clashing of elements: fire and ice, the ‘frigid, fiery, colossal waves,’ sheer and frozen.

The greengage sea, that’s different: simple as a plum and heavy like lead. A plum bob, a weight that keeps the vertical line clean and straight. A plum and the bloom of a bruise. A sea that is a plum, is as heavy as swimming in denim. A sea that is a skin, the skin of a plum the colour of old bottle-glass, sugary—greengages have an exceptionally high sugar level, some contain almost 30% fermentable sugar—and deliquescing. I can taste it: it’s good after all that odorless ice, when I read the words ‘greengage sea.’ The acidic green background in some of Georgie’s earlier works comes to mind, the soaked rawness of this colour, its depth and stillness in relation to the more turbulent forms now emerging.

Certainly, the sea keeps appearing in Georgie’s work. In the past we’ve had conversations about the tides and storms that register in her recent paintings; the stonewash aesthetic of the backgrounds; the inherent associations of wetness and solubility that come with using watercolour. We’ve talked about the works being like forecasts[2] for bad weather and rising atmospheric pressures. Not separate from this discussion, sea level rise is on all of our minds, all of the time. I think this is maybe why I am reading so hungrily about ice, painfully, and why some days even typing on this screen has come to seem like a tide swallowing the page. This conversation continues. No one argues the weather is not political, not now; every representation is breached by the reality of climate change.

Often, I am caught by the tension in this work between the restless, heavily worked backgrounds, and the hard-edged triangular structures that bisect them. White lines, incised into the paper, fly like kite tails in a rising storm. Standing in front of the works yesterday, returning now to the images on my phone, I see in this tension a system in transition, under stress. Georgie has said it before me, “For me the surface layer speaks of anxiety and chaos, but also gives a sense of space and movement. The straight incised lines contain and hold, in a protective, potentially predictable way—like interior space, like knowable systems and patterns—but simultaneously restrict and direct your eye. It is a transitional space, one of movement…The systems have to respond and change.”

These works are documents of change. The scale, context, and the way in which you make sense of this change is personal: your metaphor may be molecular, atmospheric, astronomical, psychic—or it may be something physical, felt in the gut. The greengage sea image is only one way to get here, to this present recognition of certain change. Kavan again: “It was possible that polar modifications had resulted, and would lead to a substantial climatic change due to the refraction of solar heat…a vast ice-mass would be created, reflecting the sun’s rays and throwing them back into outer space.” It is all madness, all possible.

Deborah’s dad is ninety. Later, after we’d eaten, he said the sledding was part of a cruise he had been on a long time ago. They had to fly in an aeroplane first, across the snow to get to where the dogs were, and it was expensive. I found I was relieved: it should be hard to get there, you should have to cross over oceans, break with ordinary time, before you are just once in your life flying along at the ecstatic pace of running dogs, while the ice continent melts beneath you—and the sky? The sky behaves unimaginably.

The ‘greengage sea’ comes from Ice by Anna Kavan, a book and a writer Georgie introduced me to. It’s the kind of image that almost gets lost in the turbulence of Kavan’s writing. In Ice the narrative hinges on an ice age, possibly due to nuclear detonation, and an unspecified geopolitical crisis. The often-terrifying descriptions of the climate glitter, and sometimes shatter, under their own intensity. Sometimes, they seem to relate in an oblique way to Georgie’s work, to feed from a similar light source. I read, “…sheathed in ice, [the trees] dripped and sparkled with weird prismatic jewels, reflecting the vivid changing cascades above.” You do you see it, don’t you—ice fracturing the light, the light exploding like an iris, or turning in on itself like a shell? It may be that it’s Georgie’s most recent paintings that are reflected in the iced trees, images within Kavan’s image.

Of Ice, a critic notes: “…the reader cannot distinguish between material reality and the hectic projection of the hero, who admits: “I had a curious feeling I was living on several planes simultaneously; the overlapping of these planes was confusing.”[1]I don’t really agree; the ‘hectic projection’ of the unnamed, misogynistic hero is I think clearly distinct from the material reality of the story. As a reader, disassociated from the protagonist and his predatory, narrative-driving instinct, it is the catastrophic magnificence of the environment that I experience most vividly. In this sense the book feels almost empty of human presence, certainly, of empathy. Instead of actors, there is an architecture of planes, surfaces reflecting the impossible clashing of elements: fire and ice, the ‘frigid, fiery, colossal waves,’ sheer and frozen.

The greengage sea, that’s different: simple as a plum and heavy like lead. A plum bob, a weight that keeps the vertical line clean and straight. A plum and the bloom of a bruise. A sea that is a plum, is as heavy as swimming in denim. A sea that is a skin, the skin of a plum the colour of old bottle-glass, sugary—greengages have an exceptionally high sugar level, some contain almost 30% fermentable sugar—and deliquescing. I can taste it: it’s good after all that odorless ice, when I read the words ‘greengage sea.’ The acidic green background in some of Georgie’s earlier works comes to mind, the soaked rawness of this colour, its depth and stillness in relation to the more turbulent forms now emerging.

Certainly, the sea keeps appearing in Georgie’s work. In the past we’ve had conversations about the tides and storms that register in her recent paintings; the stonewash aesthetic of the backgrounds; the inherent associations of wetness and solubility that come with using watercolour. We’ve talked about the works being like forecasts[2] for bad weather and rising atmospheric pressures. Not separate from this discussion, sea level rise is on all of our minds, all of the time. I think this is maybe why I am reading so hungrily about ice, painfully, and why some days even typing on this screen has come to seem like a tide swallowing the page. This conversation continues. No one argues the weather is not political, not now; every representation is breached by the reality of climate change.

Often, I am caught by the tension in this work between the restless, heavily worked backgrounds, and the hard-edged triangular structures that bisect them. White lines, incised into the paper, fly like kite tails in a rising storm. Standing in front of the works yesterday, returning now to the images on my phone, I see in this tension a system in transition, under stress. Georgie has said it before me, “For me the surface layer speaks of anxiety and chaos, but also gives a sense of space and movement. The straight incised lines contain and hold, in a protective, potentially predictable way—like interior space, like knowable systems and patterns—but simultaneously restrict and direct your eye. It is a transitional space, one of movement…The systems have to respond and change.”

These works are documents of change. The scale, context, and the way in which you make sense of this change is personal: your metaphor may be molecular, atmospheric, astronomical, psychic—or it may be something physical, felt in the gut. The greengage sea image is only one way to get here, to this present recognition of certain change. Kavan again: “It was possible that polar modifications had resulted, and would lead to a substantial climatic change due to the refraction of solar heat…a vast ice-mass would be created, reflecting the sun’s rays and throwing them back into outer space.” It is all madness, all possible.

Deborah’s dad is ninety. Later, after we’d eaten, he said the sledding was part of a cruise he had been on a long time ago. They had to fly in an aeroplane first, across the snow to get to where the dogs were, and it was expensive. I found I was relieved: it should be hard to get there, you should have to cross over oceans, break with ordinary time, before you are just once in your life flying along at the ecstatic pace of running dogs, while the ice continent melts beneath you—and the sky? The sky behaves unimaginably.

[1] Emma Garman,

‘Feminise your canon: Anna Kavan’, The

Paris Review, 10 December 2018, https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/12/10/feminize-your-canon-anna-kavan/

[2] The title of previous works Forecast (Detail) (2019) refers to a film in Doris Lessing’s 1971 novel Briefing for a Descent

into Hell, which takes place inside the mind of an amnesiac, exploring

fantasy worlds in connection to social and ecological issues.